Tiny Tips for Wilderness Canoe Trips

In the mid-seventies, I shared an afternoon with the famous woodsman, Calvin Rutstrum, whose flagship book, The New Way of the Wilderness, inspired my love of wilderness travel. I was heading north to Canada and had an 18-1/2 foot Kevlar Sawyer Charger (a then, state-of-the art whitewater racing canoe) on my car. I thought it was the ultimate tripping canoe. Rutstrum walked slowly around the canoe, critically peering at it from every angle. Then, he stepped away and said: "Well, it's big enough. But, frankly, I wouldn't take anything but an aluminum canoe beyond the trailhead."

I protested weakly, proposing that Kevlar would soon replace aluminum. At this, Rutsrum turned and faced me squarely. "Cliff, if there was a better way of doing things, don't you think I'd be doing them that way?"

I mumbled a polite "yes", and joined him for lunch.

Novices often perceive experts like Rutstrum as highly opinionated. But experienced trippers know that small errors can cause big problems. Here are some "little things" that can make or break a trip.

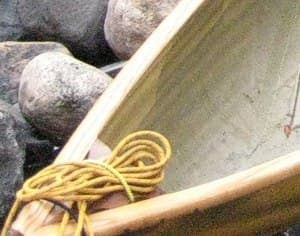

Lines coiled and ready You're paddling stern, sneaking along the edge of a dicey rapid, when a strainer suddenly appears. You pry the tail towards shore and back-paddle (backferry) furiously. As the stern runs aground, you jump out, pull the end of the coiled stern line and snub the canoe to shore. Thank goodness the rope reeled out perfectly.

Rationale: Lining ropes should be carefully coiled and inserted through loops of shock-cord on the decks. Every canoe in your party should use the same procedure for "stuffing" their lines-e.g., insert each coiled rope through the bungee cord from the bows inward, or vice versa. There's no time to think which way the ropes were stuffed when you pull the "rip cord". A wrong way pull will jam the rope in the shockcord, and possibly upset the canoe.

Stopper knot on bowline

Lining ropes should be attached to the canoe (with a bowline) as close to cut-water as possible. Leave a loop in the bowline large enough to function as a grab loop. Finish the bowline with a stopper knot or two half-hitches.

Rationale: Lines work loose on a long trip. A bowline alone isn't secure enough. A grab loop aids in hauling a canoe ashore, and in rescuing a swamped one.

Store your map before canoeing rapids

Map cases that are tied to thwarts or secured under loops of shockcord on thwarts can be ripped loose and lost in a capsize. Put your map in a secure place (e.g. inside a zippered thwart bag, etc.) before you start down a foamy rapid.

Clean the seals on waterproof boxes

Watertight boxes like those made by Pelican® and Otter® are reliable only if the seals are kept clean and free of debris. Inspect seals each time you open the box-use a wet cotton bandanna to remove trapped particles. Lubricate the seals with silicone at least once a year.

Bring twice as many stakes as your tent needs

Use the extra stakes to anchor stormlines when the wind blows up. Double-stake troublesome spots-two stakes through one hole, each at a different angle. My favorite tent stakes are 12-inch long aluminum, arrowshaft stakes. These hold rock solid on sand, gravel and tundra. Available from Cooke Custom Sewing.

Storm lines and slippery loops

When a storm blows up you may have just minutes to secure your camp. I carry 200 feet of parachute cord that has been pre-cut into 20-foot lengths. Adjusting cords during a storm--and removing them afterwards--is easy if you end your knots with a slippery (quick-release) loop.

Bring a hard case for each pair of eye glasses

It should have a lanyard or carabiner hole so you can tether it to a pack. Tighten eye-glass screws before you leave home. The tiny Leatherman® Micra has a small screwdriver that fits eye glasses perfectly.

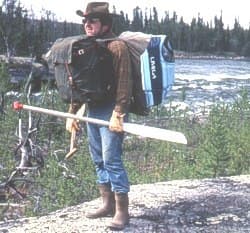

Do NOT carry packs on your chest!

Falls follow if you can't see your feet! Use a tumpline if you must double-pack.

Pack equipment the same way every day

On their 7000 mile canoe trip to the Bering Sea, Clint Waddell and the late Verlen Kruger lost part of their canoe's spray cover on a portage. Earlier in the day, Verlen had removed it from its usual place in the pack and set it loose in the canoe. He thought his partner Clint Waddell had brought the cover; Clint thought Verlen took it.

Cliff Jacobson is one of North America’s most respected outdoors writers and wilderness paddlers. He is a retired environmental science teacher, an outdoors skills instructor, a canoeing and camping consultant, and the author of more than a dozen top-selling books and a popular video on canoeing and camping. His flagship book, "Canoeing Wild Rivers", 5th Edition is the premier text for canoeing wilderness rivers. Cliff is a distinguished Eagle Scout, a recipient of the American Canoe Association’s prestigious Legends of Paddling Award and a member of the ACA Hall of Fame. www.cliffcanoe.com

Related Articles

We’ll take a look at the kit that I often choose to carry that I can access while afloat. This setup is…

Wondering what to wear when going paddling? Answer 4 quick questions and instantly learn what you need…

Some years ago at Canocopia in Madison, Wisconsin, I chatted with a young man who had recently completed…

I am a firm believer in the multiple utility of gear – getting the most out of each piece of equipment,…