Securing your Gear on Expeditions

Securing one's food from the critters of nature can be nothing more than putting the peanut butter back in the box so the raccoons don't get it. At other times, some may choose to go to lengths to suspend their food high above ground, hung between two trees. Current thinking argues that the suspended food cache doesn't always work; bears are smart and can pull ropes down, bend over trees, who knows, maybe even stand on another's shoulders and reach up to the food pack.

The reminder to pay special attention to your food is usually the metal box installed at campsites in bear country. All these precautions work best when practiced in conjunction with the simplest of critter precautions: Keep your kitchen clean and well away from the center of your camp. Store food in odor-proof container and keep them away from camp.

How many times have you seen a youngster (and a few of us old foggies) wipe our hands on our pants while eating a sloppy meal or snack? Where do those pants end up at the end of the day? Tossed into a corner of the tent, perhaps. With a nose hundreds of times more sensitive than our own, most critters will smell that "meal" from a long distance away. If you were hungry and there was a sumptuous jar of peanut butter right behind the curtain, how long would it take you to claw through to the awaiting treat? Exactly!

There are stories from the BWCA about paddlers placing their food under the picnic table with all the other hardware and gear packed around it like a crude tomb. The idea being that any critter attempting to remove the food packs will upset the well-balanced gear surrounding it and make lots of noise. Those folks are the most surprised when the next morning they come to find what's left of the protected food bags scattered around the camp with every "alarm" still in place – unmoved.

Guides in Alaska and other wild paddling areas, carry small bear-proof barrels to store food; they just fit into the aft hatch of most kayaks. Bears have learned how to pry open the metal doors on vans in parking lots so don't think your kayak's modest fiberglass hatch is immune to invasion, even if you have stuff double sealed. A food cache away from camp and boats is probably a good idea any time you are camping in the wilder regions of the country. More likely than an encounter with bears, you will probably be harassed by raccoons and porcupines that have sharp teeth and are just as determined to get food!

And not just food! Friends were paddling through the Wood-Tikchik State Park in Alaska one summer and had opted for the luxury of staying in a remote cabin a few of the nights along the course of the chain of lakes and rivers in the park. This is porcupine country and porkies just love to gnaw away at boat parts for the encrusted salt residue from handling paddles and such with sweaty palms. Even the wooden slats on their folding Klepper were targeted by the pesky porkies making storage of the boat outside impossible – they had even hoisted the double up onto the cabin roof, but it didn't slow down the critters at all. The only recourse left to them was to cram the 19' K2 diagonally from floor to ceiling in the cabin, creating an obstacle course in the narrow, 12' wide shelter.

Keeping paddles up and out of reach of the critters can be a challenge, but less so that trying to paddle with a half-eaten piece of wood. I've been in camps where paddles were lashed together and hoisted up out of the way.

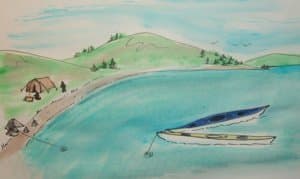

One way to make sure all your gear is out of reach of all land critters is to anchor your boat a few dozen yards off shore. (taking tidal fluctuations into account). This offshore anchoring method used to be called a "Siwash anchoring" but I am not sure that this term is favored any more. This method involves securing a boat to a line that enables it to be retrieved back to shore from a free-floating mooring.

The second part of the Siwash method involves a second line attached to a rock large enough to serve as an anchor. It is attached to an anchor line and the coiled line and rock are balanced on the fore deck of the kayak or canoe. When the boat is in position from shore, the line is yanked so the rock falls off into the water. The "anchor" line is long enough to allow for tidal fluctuations. It goes without saying that you had better learn how to tie a few knots. I had a hard time finding any information on this method. Part of the problem may be that the term "siwash" is considered a derogatory term in some regions of the Pacific coast.

It is a good idea to secure your kayak or canoe no matter how secure it may seem. Wind can toss a boat around smashing it into rocks or logs or even out to sea. A simple bow line around a huge rock or limb of a tree is all that is usually needed. Even tying boats to each other can be enough to keep them from scattering.

The most radical effort to secure a boat is during severe weather such as hurricanes and typhoon winds. A friend who ran a touring business in Hawaii was faced with securing his kayaks against an approaching windstorm. Tying boats to trees that could be pulled up by their roots is not an option. Likewise storing them in buildings that collapse or have their roofs ripped off is not an option either. What to do?

At the risk of having a tree fall on his boats, the resourceful outfitter laid them all out in the front yard of his house and filled each one completely up to the cockpit rim with water! Basically he sunk them on land. With water weighing eight pounds per gallon and easily 50-70 gallons in the cockpit area alone (assuming bulkheads), one could fill the cockpit with over 500 pounds of ballast. You’d run the risk of something being blown into the boat or falling on it, but little else.

Lastly, the simple task of securing a boat to your car can limit your concerns if you always use straps and ropes and NEVER bungee cords to secure your boat. Boats, kayaks especially, seem to always ride well facing into the wind (or with the pedal to the metal); it’s those nasty quartering or side winds that really knock a boat around. It seems no matter how smart you think you are, there is a critter out there that is just a little bit smarter. So to, no matter how strong you think something is secure, Mother Nature can find a way to loosen it up and toss it around. It never hurts to ask around, for both the critters to watch out for and for advice on how to best secure your boat against the local, natural residents.

Tom Watson is an avid sea kayaker and freelance writer.

His latest book, "Kids Gone Paddlin" is available on Amazon.com.

He is also the author of "How to Think Like A Survivor"

Related Articles

This a follow up to a video I did where I talked about differences that you may find in dry and semi-dry…

Can you use a Greenland Paddle in a Recreational Kayak? I received this question recently from a…

Learn how to stay comfortable on the water when fishing in the cold. When you stay warm and…

Mention guns and canoe trips in the same breath and some folks are apt to go ballistic. Still, if you're…