Miracle on the Chesapeake - A kayak angler's survival story

Kayak angler Sean Danielson’s father insisted he wear a lifejacket. Years later, that advice would save his life.

Sean Danielson is a lucky man.

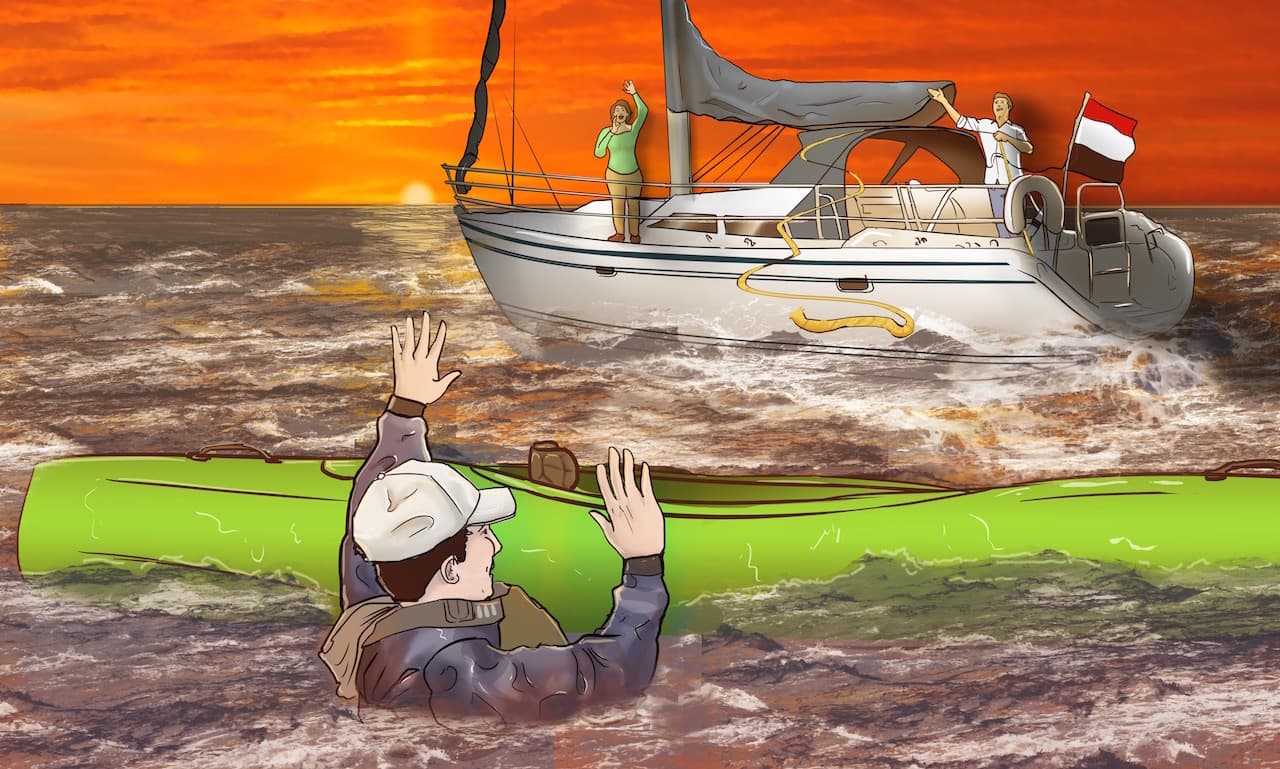

After nearly three hours in the frigid waters of Chesapeake Bay, the kayak fisherman was hypothermic and barely conscious. The sun had just set, and if Lana Lohe hadn’t put her camera down at that instant and caught the unusual streak of green in the corner of her eye, then Sean Danielson would certainly have died that April evening. The mere fact that Lohe and her husband Robert passed that spot at that moment, after 18 days sailing from the Bahamas, was an extraordinary coincidence. A miracle, some would say. After all, theirs was the only boat Danielson had seen all day.

Sean Danielson is indeed a lucky man, but there’s a lot more to the story of his capsize and rescue than luck, or the everyday heroism of those who pulled him from the freezing bay waters. And, like many things in life, it began with a little fatherly advice.

Danielson grew up fishing with his dad, and when he moved home to Connecticut to help after his father broke a hip a few years ago, they picked right up where they’d left off. Often, they fished from kayaks, and on those hot summer days when Danielson would slip off his life jacket and set it behind his seat, his father would gently chide him.

“I mean, we were 100 yards from shore, and the lake was like glass,” Danielson says. “But he always said, ‘Sean, that kayak isn't very buoyant. You know you should keep wearing that life jacket.’”

“A big wave that came from the side and rolled me over, and all of a sudden I was in the water.” — Kayak angler Sean Danielson

The lesson stuck, and when Danielson moved to Maryland and began fishing the sometimes-turbulent waters of Chesapeake Bay, he never failed to wear his lifejacket. As the striped bass season neared in the spring of 2018, he became obsessed with catching the hard-fighting trophy fish from his kayak. The books he read and the old-timers he talked to all had the same advice: Fish the drop-off, where the depth goes from about 10 feet to 40 feet or more. That’s where the stripers are.

He bought a depth finder, and one Saturday that April he paddled out into the bay for what seemed like miles. By the time he got back to the dock his girlfriend had already gone home—she thought he’d decided to paddle all the way across the bay. In fact, he hadn’t gone far enough. He didn’t find the depth line.

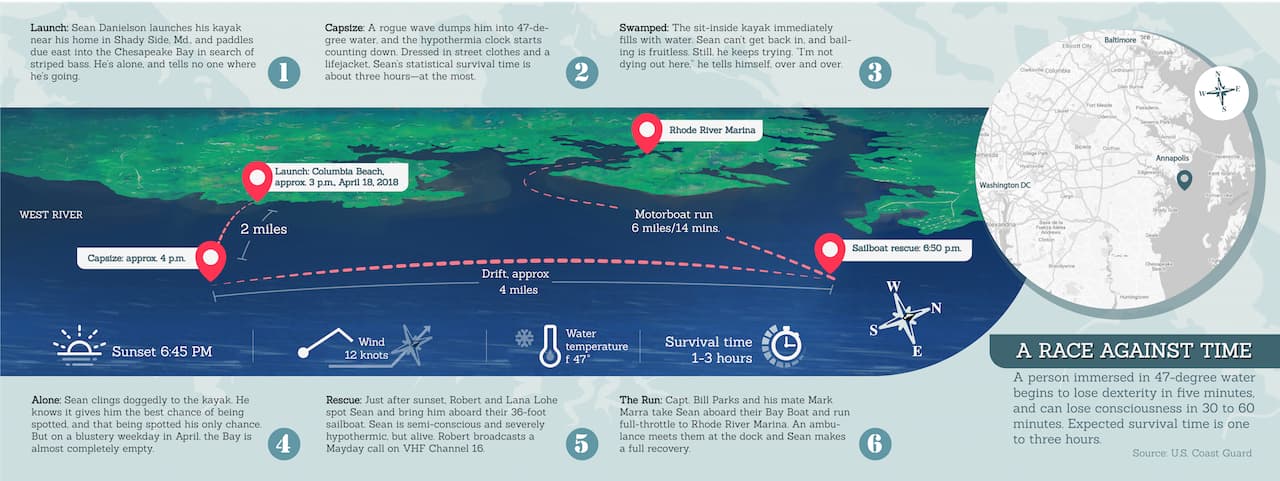

That Wednesday he tried again, starting at about 3 o’clock in the afternoon and paddling due east into the bay. This time he didn’t tell anyone where he was going. Dressed in jeans and a long-sleeved shirt under his lifejacket, he was comfortable enough in the 55-degree weather. The water temperature however was just 46 degrees. Danielson, who had done almost all of his kayaking on protected lakes, took a few minutes to find his paddling rhythm in the choppy bay. “It was awkward at first, but I learned to just relax, keep my center of gravity low and just kind of go with it,” he says.

He was about two miles out when the wave caught him. “I didn't see it,” he says. “There was no warning, just a big wave that came from the side and rolled me over. It just happened instantly, and all of a sudden I was in the water.”

From that instant, the clock was counting down.

In 46-degree water, a healthy man of Danielson’s size can expect to survive anywhere from one to three hours. It’s an inexact science, but the clock was counting down.

Thanks to his lifejacket he wasn’t at immediate risk of drowning, which is the leading cause of kayaking deaths. But the next most common cause of kayaking deaths is hypothermia. In 46-degree water, a healthy man of Danielson’s size can expect to survive anywhere from one to three hours. It’s an inexact science, but there was no uncertainty about the setting sun. It would slip below the horizon in less than three hours, taking all realistic hope of rescue with it.

Danielson took stock of his situation.

“I remember specifically telling myself to stay calm. I told myself, ‘It's OK. Flip the kayak over and get back in.’” But when he righted the kayak, I was completely full of water. He was paddling an Old Town Vapor 10, a 10-foot sit-inside kayak that retails for a few hundred dollars. A reasonably athletic kayaker can scramble aboard a sit-on-top kayak after a capsize, and with practice it’s possible to remount a sit-inside kayak if it’s equipped with bulkheads dividing the hull into separate watertight compartments. The task is almost impossible in a kayak like Danielson’s, a sit-inside with no bulkheads.

He thought about leaving the kayak and swimming for shore, but decided that staying with the kayak gave him the best chance of being seen, and that being seen was his best chance of survival. Realistically, it was his only chance.

“I flipped it over and it was so full of water it just flipped over again. I kept flipping it over again and again and again. I’d turn it over, and it would be sitting below the surface,” he says. “I started to realize this wasn’t going to work.”

He scanned the horizon for boats, but saw none. Nobody knew he was out there.

He thought about leaving the kayak and swimming for shore, but he decided that staying with the kayak gave him the best chance of being seen, and being seen was his best chance of survival. Realistically, it was his only chance.

“In the beginning, I told myself I am not going to die in the Chesapeake Bay. It’s just not gonna happen,” he says. For more than two hours, as the sun tracked toward the horizon, he kept trying to right the kayak. He tried straddling the upside-down hull, but couldn’t keep his balance. He found a cup floating in the water and tried to bail, but it was no use.

The bay was completely empty, except for the container ships ghosting down the shipping channel. They were as far from Danielson as the shore—about two miles—but still he waved and wailed on the orange plastic whistle clipped to his lifejacket.

“As time went on I was getting colder,” he says. “I was getting tired, but I was not going to stop flipping that kayak. I said, ‘I’m not going to die not trying.’”

That same evening Lana and Robert Lohe were motoring north in their Catalina 36 Our Diamond. They’d spent the previous six months living aboard the 36-foot sailboat in the Bahamas. Now, after 18 days travelling up the Intracoastal Waterway they were barely an hour from their Annapolis home.

“We were reflecting on what a wonderful trip we’d had, and I was taking pictures of the sun setting—it was a beautiful sunset—and just when I was getting ready to set the camera down I saw something,” Lana Lohe says. She thought it looked like a piece of carpet; to Robert it looked like a patch of seaweed. But when she looked again with the binoculars she saw an arm moving.

“I told Robert, ‘I think there's somebody in the water. Oh my gosh there's somebody in the water. Turn! Let's go!’” she recalls. Now they could hear Danielson’s whistle, and see that the splash of color wasn’t carpet or seaweed. It was an overturned kayak.

The couple immediately went into rescue mode. Our Diamond was motoring, but even with no sails to douse, it took a few passes to get a line to Danielson, and then for Robert to grasp his hand and help him to the swim ladder on the vessel’s stern. Next he made a radio call on VHF Channel 16: “Mayday! Mayday! Mayday! This is sailing vessel Our Diamond. . . .”

The Coast Guard responded instantly, and as Robert reported his location and the nature of the emergency he looked over his shoulder and saw that Danielson was still in the water clinging to the ladder. He was too cold to move. Robert set the radio down for a moment, grabbed Danielson under the armpits and heaved him aboard. Lana bundled him in a fleece blanket. He was safe for the moment, but still dangerously hypothermic. He needed to get to a hospital, and fast.

The moment Capt. Bill Walls heard the Mayday call, he pointed his 29-foot bay boat at the only sailboat in sight. As he closed the three-quarter-mile distance to Our Diamond, he hailed Robert on the VHF, asking if he could render any assistance.

Robert said yes. Our Diamond makes about 8 knots flat-out. Walls’ motorboat is nearly four times that fast, and time was of the essence. They decided to transfer Danielson to the faster boat, a feat that required no small measure of strength and seamanship.

They brought the boats together stern-to-stern, and with Lana handling the lines the three men—Walls, his mate Mark Marra and Robert Lohe—passed the semiconscious Danielson into the motorboat.

“I normally don't run a boat that hard on the first trip of the year but I had her wide open, because I knew he needed help and he needed help quickly,” Walls says. Danielson was “reddish purple” and falling in and out of consciousness. Marra got him out of his wet clothes and into a dry sweatshirt, then kept him talking. Whenever Danielson started to drift off, Marra would slap his cheeks, his shoulders, his legs. He kept up a running banter, even cracking jokes.

“We asked him what he was doing out here, and he said ‘fishing,’” Walls says. “So we asked him if he caught anything.”

As they raced for shore, Walls and Robert Lohe worked the VHF. When Walls roared in to Rhode River Marina it was already full dark, and the lot was full of flashing lights. Danielson was admitted to the hospital with a core body temperature of 80 degrees, and over the coming days he made a full recovery. He even bought a new sit-on-top fishing kayak to target largemouth bass on inland waters.

So yes, Sean Danielson is indeed a lucky man.

If you’ve been reading closely, you may be keeping a mental checklist of the cardinal safety rules Danielson ignored or perhaps didn’t even know. He wasn’t dressed for cold-water immersion. He paddled alone, and didn’t tell anyone where he was going. He lacked experience on open water and his kayak, to put it charitably, was little better than a pool toy.

But here’s the thing: Most kayakers have made those same choices. Many kayakers have made them recently, and often. So though Sean Danielson is a lucky man, he is not an unusual one. Any one of us could find ourselves in his place, or that of the people who saved his life. If we do, we can only hope we respond with Danielson’s determination, or the selflessness of his rescuers. Walls says anyone would have done the same in his shoes. “It’s the golden rule. You treat people how you want to be treated, and you help them in times of need.”

In the end, that’s why Danielson agreed to sit down in front of a camera and recount his ordeal. To pay it forward. Because for all the things he got wrong, the one he got right—wearing his lifejacket—provides a lesson all of us can live by.

Related Articles

Wondering what to wear when going paddling? Answer 4 quick questions and instantly learn what you need…