River Hazards and How To Survive Them

I learned the hard way, why, at certain times of the year – during spring flooding primarily – our local river, the Pomme de Terre, is called the Pomme de TERROR! High spring waters flowing down its narrow, meandering channel clogged with fallen cottonwoods and other debris create ongoing hazards around nearly every bend.

Such it was one afternoon when I found myself in my canoe, forced precariously sideways against a dense network of skeletal-like branches of a downed cottonwood. A narrow opening immediately adjacent to the high cutbank was my only possible escape route if I could free the boat from the powerful force of the swollen current.

While trying to wiggle free with a slight downstream lean, I lost my balance and did a face plant into the tea-colored water. The canoe flipped over, caught water and was forced, bow first, into the muddy embankment. Like a spaghetti noodle in a strainer, I was being pushed to the bottom against a nasty jumble of branches.

I groped through the water and found a handhold on the gunnels of my submerged canoe. I yanked it backwards off the bank and could feel the bow swing around and be pulled downstream through a narrow hole in the branches. As the current swept the boat past the tangle of branches, I pushed off the bottom and followed the canoe through the hole into open water downstream. I popped to the surface gasping for air. Phew!

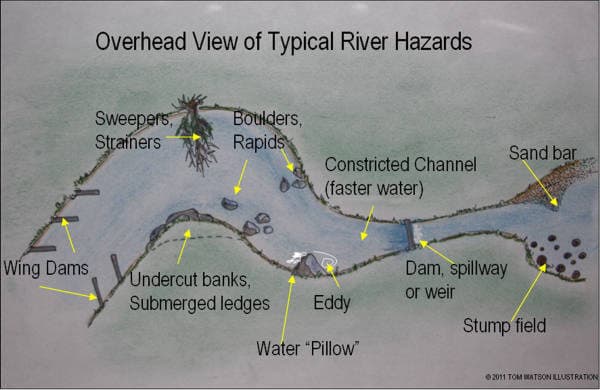

Each type of water whether expansive oceans and lakes or meandering streams and rivers have their own unique hazards that challenge the paddler. Some are natural such as currents, rip tides, rocks, reefs, narrowing channels, winds and myriad natural obstacles (surface and submerged). Other hazards are man-made (dams, weirs, spillways, structure abutments, stump fields, barge wake) that can also cause the flowing waters to act in ways that can be very dangerous to paddlers of all skill levels. Of these, arguable none present the diversity and intensity of hazards as do the flowing channels of water we call rivers.

Reading the River

One of the first of many river "hazards" we are introduced to as beginning paddlers is the current itself. Smooth, nondescript flowages of water can suddenly twirl and tumble causing disruptions in the surface and counter currents that can spin a boat around. We discover that rocks can create a wide array of challenges that disrupt the smooth water of passage. They can be giant granite monsters squatting defiantly right in front of us. They can be a string of boulders, clustered together in such a way so as to form a gentle series of riffles, or a continuous set of waves (like a corduroy roadway of water called a wave train). They can also turn the current into a churning cascade of turbulent water. Most often we learn to work our way through them, sometimes leaving submerged rocks decorated with telltale silver streaks from our aluminum hulled canoes.

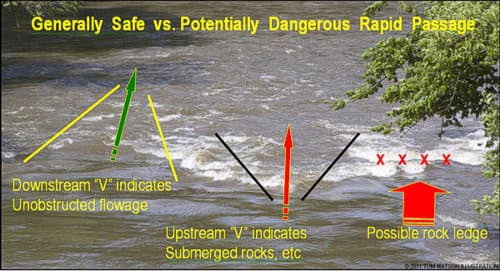

We learn to "read" the river to tell us which course to take through a rapids such as the downstream pointing "V"-shaped flow of smooth water that indicates a clear channel through the rocks. Conversely we learn that rocks lying just under the surface causing that water to boil and tumble forms an upstream pointing "V" – a sign of caution for most – or an inviting challenge for the more seasoned and skilled paddler.

River Hazard Terms

The list of river hazards is quite extensive. Here is a glossary of the most common hazards one may encounter on river systems across the country:

- CURRENT – Ever present flow of the water - from timid to turbulent –where volume, channel width and gradient (see definition below) all affect the characteristics of a river. Current is usually slower along the inside bend of a river, faster along the outside bend. Also current is faster on the surface due to less friction than along the bottom of the channel.

- GRADIENT – The steepness of the river bed, expressed in feet/mile (an average).

- RAPIDS – water flowing over an obstruction, causing turbulence. Most often formed by boulders below the surface.

- HOLES – water flowing over a ledge or rock creating a void, can trap objects held in the circulating flow/hydraulics created.

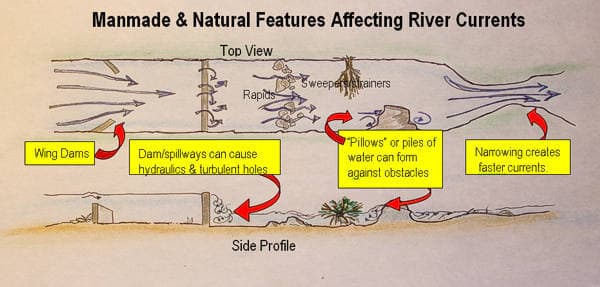

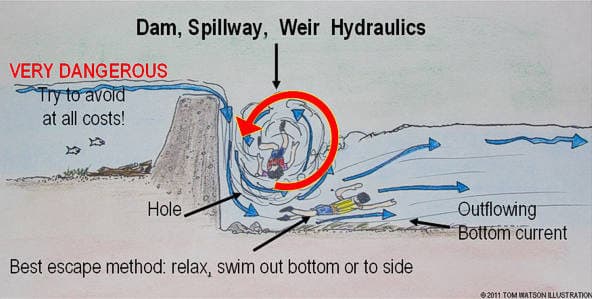

- HYDRAULICS – Water circulating on top of itself – evident by the churning of water below a dam or spillway. Often associated with other hazards such as holes and breaking waves.

- EDDIES – Water rushing around obstacles, circulating downstream, towards shore in a reverse current. Current flows to fill void created by flow of water. Sometimes violent eddies form whirlpools.

- EDDYLINE – boundary between the circular eddy and the downward current flow.

- POUROVER - Think of it as a vertical eddy, water flowing over a rock, ledge or manmade horizontal structure (dam, spillway, weir) creating a "hole" below the obstruction.

- DROP – Water dropping straight down – a waterfall is a classic example.

- CONSTRICTED WAVE – As flowing water is constricted – by a narrowing channel - it begins to move faster. The compressed water sometimes forms waves.

- WAVETRAIN – a series of non-breaking waves.

- BREAKING WAVES – the top of a swell that collapses down on the upstream side of the wave (often referred to as a "stopper").

- PILLOW – Water that is piled up by the current against an obstruction that is not entirely submerged. Water is compressed but flows around it.

- FERRYING – causing boat to move laterally across the current, usually to maneuver around obstacles, work eddylines, etc. "Back" ferrying puts the bow pointing downstream; "Front" ferrying faces the bow upstream. In fast current, the ferrying angle should be narrow; in slow current – broader.

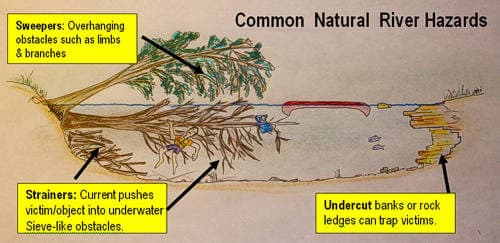

- UNDERCUTS/POTHOLES – submerged hazards that don’t usually affect passage overhead but can trap a capsized paddler under the edge of a riverbank or rock ledge, or entrap a victim against a rock or in debris settled into a pothole.

- ENTRAPMENTS – Anything that can snag/hold one underwater, from the force of water preventing them from swimming free or clothing/items becoming snagged on the obstruction (branches, rock points, etc.).

- SWEEPER – branches hanging low over or into water that can sweep a paddler from the boat.

- STRAINER – Often used to describe a sweeper under water. Branches act like a sieve that keeps victim/boat/gear from passing through. Oftentimes loose objects get snagged by strainer branches, thereby holding victim below the surface.

- DAMS – Probably the most formidable of all man-made structures. These must be portaged. To go over a dam is to permanently terminate your existence! Dams and dam-like structures (weirs, spillways, ledges) come in a variety of sizes but all form an obstruction completely across a river. Severe hydraulic action occurs at the downstream base of these structures.

- WING DAMS – These are small, dam-like structures protruding out from the bank of a river to define the channel. They are angled downstream at varied intervals.

- CLOSING DAMS – Not so much a hazard as a nuisance. These go from shoreline to shoreline completely blocking a side channel.

- BRIDGES, ETC. – The bases of these structures can create eddies, collect debris that can act like strainers and cause the current to react in myriad ways.

- STUMP FIELDS – As part of the creation of pools behind dams, trees were cut prior to the flooding of lowlands. Many acres of stumps lie submerged just below the surface throughout many of these pools.

- TRAFFIC WAKE – Barges are restricted to the main channel in rivers with dredged channels. Their wake and churned up water can be dangerous to small craft. Stay clear of commercial river traffic.

- OTHER HAZARDS – common to all bodies of water are the natural elements of wind, lightning, fog and even the water itself (hypothermia, for example).

Basic Hazard Prevention and Recovery Techniques

Prudent paddlers will want to develop skills that can be called upon to deal with a wide variety of challenging obstacles along the river. Prevention is far preferred to recovery in all cases. Better to avoid a problem than try to paddle out of it. Oftentimes using the technique of ferrying, one can swing around or out of a potentially compromising situations. Therefore it's important to know a variety of back paddling strokes – and how your craft reacts to those strokes – so you can call upon that invaluable information and expertise when needed.

Being trapped in a strainer can be a terrifying experience. If forced against a downed limb, it is sometimes advisable to climb forward onto the stouter branches and work your way to shore – or beyond the downfall to open water downstream again. If you are forced below the surface, try swimming downstream using your hands before you to part the branches ahead of you.

The hydraulic somersaulting tumble at the base of a dam is most often a fatal predicament. The force of the water keeps an object recycling over and over in the boil of the current. The best chance at recovery is to relax (that alone will take a mighty serious effort given the circumstances) and try to swim deep to get into the slower, downstream current that does flow out of such holes.

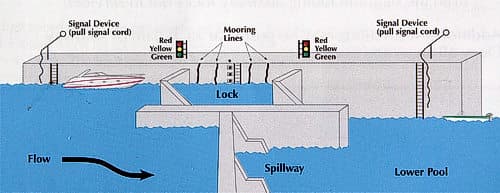

Lock and Dam Protocol

Approaching a lock and dam complex is usually not hazardous if you stay out of the restricted areas (On the Mississippi River, for example, those areas are 600' above a dam, 150' below). Passage through these humungous structures is quite simple and straight forward:

approach/check the light signals:

- no light = in use, approach guide wall, signal with pull cord;

- red light = stand clear, do not approach

- yellow light = approach lock area under full control

- green light = enter lock, pull to side wall, hold onto rope (DO NOT TIE TO BOAT!).

Upon completion of the lock cycle, there will be either a PA announcement, a short toot of a horn or a visible hand signal that it's clear to exit the lock. There is no fee for this "first come-first served" process. You can contact most dam operators via VHF channels 14 and 16 to learn the status of the lock.

General River Sensibility and Other Safety Tips

Don't forget to study up on general river regulations and rules. It is important to at least understand the basics of the buoy system and general principles of river navigation too (see previous Guideline article, "Buoy & Marker Messages").

In his book "Basic Essentials – Canoeing", outdoor river guide and canoeing pro, Cliff Jacobson cites several common mistakes made by canoers:

- Don't stand in water more than knee deep. Strong currents can knock you down, rocks can trap your feet - grab the upstream end of your canoe, try to swim to shore.

- If caught against a rock – lean downstream. If you have to exit the boat, get out upstream unless you can climb up onto the rock.

- Not scouting out rapids even if you think you know the river, changing water levels change everything!

- wearing lifejacket unzipped – makes it easy to get snagged on branches, rocks, etc.,

- wearing high-topped shoes. If foot gets caught in rocks, it may be impossible to remove foot from shoe. Wear appropriate, easy-to-discard footwear.

- Going barefooted: sharp rocks, broken glass, other nasties can cut your feet.

- Not using a glasses retainer – you won’t be able to see other hazards if you lose your spec's!

- running rapids with something tethered around your neck (Swift Army knife, compass, whistle) and having it get snagged on your boat – or an obstacle- during a capsize.

- Running rapids sitting down instead of the lower center of gravity, more in-control kneeling position.

These mistakes can be minimized and mitigated by learning and practicing some essential paddling skills including a variety of paddling strokes, knowing the rules and regulations for riverways, learning and practicing on-water techniques (ferrying, crossing eddylines, back paddling), being aware of hazards and knowing how to spot them, always acting responsibly and respecting the rights of others, using a float plan, and anticipating other traffic's actions and intents if possible.

A great source of river characteristics, boat handling, safety and rescue techniques is, "River Safety – A Floater's Guide" by Stan Bradshaw (published by The Lyons Press). Other references include each state's DNR office for information on its local waters, including hazards and safety tips. Check out the U.S. Coast Guard & Coast Guard Auxiliary site for a plethora of river information.

Lastly, local river knowledge is probably the most reliable and current for those areas beyond the realm of national/regional agencies. Check for local paddling clubs if you seek information on rivers unfamiliar to you.

Above all be careful, have fun and be safe. The best way to deal with a river hazard is to avoid it altogether.

Tom Watson is an avid sea kayaker and freelance writer. He also posts articles and thoughts on his website. He has written 2 books,"Kids Gone Paddlin" and "How to Think Like A Survivor" that are available on Amazon.

Related Articles

With good technique and a little practice, regardless of size or strength, most people can perform a…

Driving a car safely involves much more than merely focusing only as far ahead as the taillights of…

Wondering what to wear when going paddling? Answer 4 quick questions and instantly learn what you need…