Minimizing the Aches and Pains of Flatwater Paddling

~A Paddler's Post submitted by Gregg Jackson~

Flat water paddling is a great pleasure—a journey into nature, a melodic exercise, and a meditation. But it also can be uncomfortable and even painful, particularly as we age.

In my 73rd

year, the pain began to cancel the joy. I had to innovate or retire. A few years of intermittent reading, thinking, and testing have identified 13 things that help. Bodies vary, but some of the following might assist you.

1) Pick the paddle carefully

In terms of paddling ease, taking 10 ounces off our paddle is probably the equivalent of taking 10 pounds off our kayak—and it costs less. We not only have to hold the paddle up for long periods of time but we must redirect the mass of the blades up and down, fore and aft, about 40-60 times per minute. Even without putting the blade in the water, that can be a strain on the shoulders—try stand up with your paddle in hand and air-paddle for fifteen minutes straight.

Well-established manufacturers make kayak paddles down to 18 oz. (510 g.) for calm conditions and 23 oz. (652 g.) for general use. Canoe paddles can be two-thirds those weights. Paddling effort is also reduced by using the shortest paddle that is suited to the body, paddling style, the craft, and paddling conditions. To determine the optimum length for a double-bladed paddle, grip your current one normally and check the feel when paddling, then move both hands 2” (5 cm) to the left and check again. The feel on the left will be similar to paddling with a 10 cm shorter paddle, and the feel on the right will be like using a 10 cm longer paddle. Those with modest upper body strength might also benefit from smaller blades.

2) Use a light touch

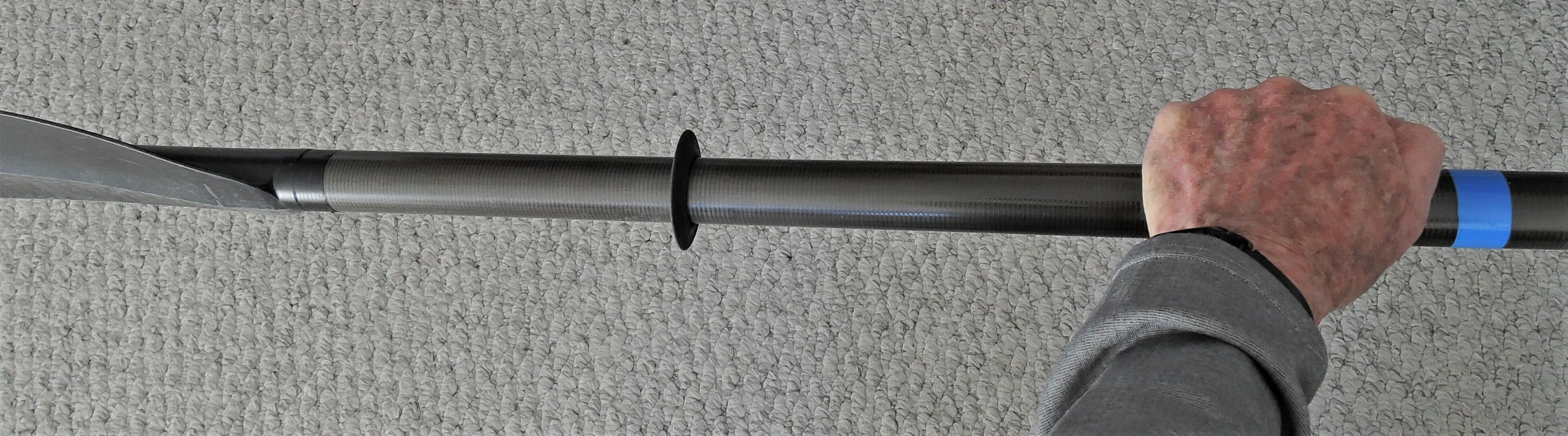

Clinching our hands for long periods of time can trigger soreness all the way up the forearm. For gnarly conditions, hold tight. For the rest of the time, cup the hand to resist the force of the power stoke, but don’t squeeze with the finger tips. A few paddle manufacturers offer a smaller diameter shaft to accommodate small hands. They also make bent shafts, which some people swear by and others swear at. The following can facilitate a light handhold: Wipe the grip positions with alcohol swabs to remove body oil, add a wrap of plastic tape just inside of the optimal position for each hand to help show when the hands have slipped off target, and add tacky tennis “overgrip” tape at the hand-hold positions. If you tend to blister at the base of the thumbs, try sometimes holding the shaft with all five fingers on top, as shown here.

3) Make the seat agreeable

Seats can be a pain in the butt, legs, and back. No seat will be comfortable for everybody. The key characteristics are the contour, softness, height, tilt at the front edge, and back position. Some seats allow all but the first and second to be easily adjusted, and some require improvisations that can be found on the web. Tilting the forward edge of the seat up five or ten degrees will often add to the comfort. If the tailbones still hurt, try adding about a half-inch (1.2 cm) thick sheet of resilient closed-cell foam—yoga mats often work. To provide good lumbar support and allow shoulder rotation for forward paddle strokes, most seat backs have to be lowered all the way and rotated forward to upright. The seat should bear against the spine at about the belt line. For extra lumbar support, try add a short strip of foam, taping it in position. Experiment—and it may take several tries.

4) Dress for success

Upper-body clothing can contribute to paddling discomfort in three ways:

- Like the paddle, long sleeves add weight to our arms and thus strain on the shoulders—even more so when the sleeves become wet

- As we make a forward stroke on one side, the fabric of a shirt often binds at the arm pit, across the back, and then at the elbow, adding further strain

- The clothing can contribute to over-heating, or conversely, inadequate retention of body heat.

The optimum solution in hot weather is to wear a high-wicking tank top, widely sold as exercise clothing, one size up from our normal size. If that doesn’t comply with your personal dress code, go with a high-wicking short-sleeve top of a stretchy material, one size up, preferable with cooling technology. Columbia’s “Zero Rules” ticks off all the boxes, and mine has endured three years. As the weather moderates, ditch the cooling technology but stay with short sleeves and add a fleece neck gaiter and beanie—they are easy to remove if the temperature warms. When additional layers are needed, add a fleece vest, thermal long johns, and, when not using a spray skirt, splash pants, but don’t plan on removing any of these if the weather warms, without first going ashore. If one’s arms are still cold, try a synthetic base layer for outdoor sports with gusseted or articulated underarms so that there is little pull on the fabric when the arm is raised to plant the paddle. When laid flat, the arms should angle down about 20 degrees from horizontal versus the 40 degrees of most tops—as shown below. A Patagonia Capilene Midweight Crew has served me well. On a hot day, a brief rain shower can be invigorating but a long squall can cause shivering, so a rain jacket large enough to fit over the PFD is comforting. I cut the arms off mine, which makes it easier to don and doff and eliminates the water that otherwise would enter through the cuffs and pool at the elbows. If more than all this is needed, it is probably time for cold water protection.

5) The big chill of cold-water garb

This gear can save lives by protecting against cold shock, cold incapacitation, and hypothermia, but it adds to the discomfort of paddling. The more protection that is offered by the various options, the more discomfort they usually induce—by adding weight to our arms, binding during the paddling strokes, and precluding easy adjustments of the warmth as the air temperatures change. The least obtrusive are wetsuit shorts and neoprene caps, which might protect against cold shock and slow the onset hypothermia when water temperatures are in the low 70s, but probably not below that. Wetsuit long pants provide a little more protection without much more discomfort. Farmer John wetsuits (long pants and an attached vest top) provide more protection and seem ideal for paddlers because they have no sleaves. I have one from a reputable manufacturer that appears thoughtfully-engineered, is made of extra stretchy neoprene, and fits perfectly when I am standing. But when I sit in a kayak, it feels like several wraps of a super-wide ACE bandage, hindering my abdominal breathing and torso rotation. The next level up in protection and discomfort is a full wet suit that also covers the arms, and I have no interest in even trying one. How about drysuits? Drysuits are to be worn with thermal layers under them. Together they add weight, binding resistance, and temperature regulation problems, and the neck seals make some people feel that they are being strangulated. What to do? We have four general options: Power through the discomfort that this gear exacerbates, wear it but accommodate by reducing our miles and time on the water, skip the protection and take our chances, or play it safe and stay ashore when the water is below the danger point. Before making a decision, it would be wise to review the materials at Cold Water Boot Camp and/or The National Center for Cold Water Safety.

6) To glove or not to glove?

Gloves can alleviate paddling soreness and aggravate it. They help fend off blisters, absorb UV rays, provide warmth, and sometimes facilitate the grip. They also require discernable grip force just to bend them around an imaginary paddle shaft and they add weight where we least want it, which is doubled when wet. I usually paddle in the morning and don’t put gloves on until the sun rises high or a blister seems to be forming.

7) Double-shade the eyes

Sunlight, both direct and its reflected glare off the water, can cause eye strain, headaches, and vision damage. Aviator shades and a baseball cap may look “American cool,” but they don’t work when the sun is coming from either side. Better protection is afforded by wrap-around sunglasses and a full-brimmed hat. Get the glasses with at least 99% UVA and UVB protection or “UV 400 nm.” Add a glasses strap. Choose a hat having stiff all-around brim of about 3” (8 cm), with dark fabric on the underside to absorb rays reflected up from the water. One that floats and has a chin strap is preferable. If a retailer’s photo shows the brim to be wavey or says it can be snapped to the head piece, the brim will probably flutter annoyingly in a breeze.

8) Start slowly and build up

The cardinal safety rule of all rigorous exercise is to warm up gradually. After launching, start out at half-speed and build up over ten minutes. If the launch site doesn’t permit that, do shore-side exercises to warm up the cardio-vascular system and the arms. Do the same after substantial breaks.

9) Free the legs

Being folded at 90 degrees with our legs almost straight, as required by most touring kayaks, is a prescription for leg, butt, and back pain. Some people can do it for hours, but others can’t, and age makes it harder. There are things that can help in addition to adjusting the seat:

- Remove the shoes or sandals to lower the heels

- Move the heels inboard toward the centerline of the kayak so the feet splay and allow the knees to bend laterally

- Move the foot-brace aft so the knees bend some vertically

Simulate these adjustments by sitting on the floor with your back flush against the wall. Place the ankles 14” apart, point the feet up, and gently slide the heels until the legs are straight or uncomfortable. Then make each of the above-mentioned adjustments. The problem of course, is that touring kayaks’ narrow hulls and low decks severely limit how much knee bend is possible. Still, small adjustments in this manner might reduce the discomfort, and if not, it is time to consider getting a kayak with a greater beam and/or higher deck. Stats for those dimensions are only suggestive when it comes to leg freedom, and thus a trial outing for at least half of your normal paddling time is advisable.

The most comfortable sit-in kayaks with two bulkheads that I have encountered are the Perception Carolina 12 and Carolina 14, primarily because the cockpit is long enough 39” (99 cm) that even tall paddlers can raise both knees at once for pain relief, but it also has knee pads under the decks that allow locking-in during rough conditions. Spray skirts are available, but the large forward area will not hold up if big water comes over. When paddling 7-8 miles, I need to remove both feet from the foot braces and raise the knees about 2” (5 cm) above the coaming for about half the time. Three things keep my body from sliding forward: The seat bottom is a grippy material and pitched up at the front; the knees rest on coaming pads where the cockpit sides are curving in (shown below); and the feet rest on the aft end of a tubular bag, 7.25” (19 cm) in diameter, stuffed with a survival kit and shore shoes, that has been pushed under the foredeck, between the foot braces, until it butts against the forward bulkhead. This might seem mickey-mouse, but I can paddle 3 miles per hour when positioned like this if there is little head wind—adding several miles to my comfortable range.

10) Vary the paddling stroke

Most experts distinguish between “high angle” and “low angle” forward paddling, and suggest that individuals are better suited to one or the other. When we find one hurts and the other doesn’t, that’s good advice. But some people might benefit from varying between both to minimize the chances of repetitive stress injury and because the high angle is more powerful and efficient while the low angle places less strain on the shoulders. Other things that might reduce paddling discomfort are placing the hands a little closer or farther apart on the paddle shaft, pushing forward with the raised hand during the power portion of the stroke, and using more or less trunk rotation. People with short torsos who paddle beamy recreational sit-in kayaks are forced to use a low-angle stroke to avoid having the paddle shaft scrape on the vessel, and they will find that raising the seat bottom 1-2” or adding a cushion will allow them to paddle more efficiently—with less effort for a given speed or distance. The cushion should be of closed-cell foam, with a tacky surface.

11) Optimize the paddling breaks

To reap the maximum benefits from a short break, don’t just pause the paddling but relax the entire body. Place the paddle across the craft, holding it with an eased grip. Consciously relax the legs, torso, arms, shoulders, and neck. Breathe deeply. I fail to do this intuitively and must coach myself. In addition, lower back pain sometimes can be eased by briefly scooting the butt forward and arching the back.

12) Secure the craft before getting in and out

Several sources suggest that most flat-water kayaking injuries happen when getting in and out of the craft. My closest brush with disaster over the past 500 hours of paddling was when getting out at a floating dock. The kayak began moving away and my butt almost missed the dock, which would have sent me sliding on my spine down the dock edge until my head hit. Most vessels are tied at both their bow and stern when parked parallel to a dock, but kayakers cannot reach those points. They could run a line from approximately amidships on the kayak to the dock, but normally there is nothing to which it can be secured on the yak. That can be remedied by securing an eyestrap on each side of the deck, about 32-35” (81-89 cm) forward of the seat-back and about 1” inch inboard of the maximum beam there. The Harken 38 mm low-profile eyestrap works well. I have a knot in my bowline 4’ (1.2 m) from the loose end, and run that end through the eye closest to the dock and secure it tightly to the dock cleat—as shown below. When preparing to get out, place the feet on the kayak bottom about 1” off center toward the dock side. The rope holds the yak against the dock and keeps the off-center weight from tipping it. Make sure the eyestraps are positioned far enough forward that your paddle and knuckles won’t rap against them when paddling. Attach them with washers and lock-nuts, and use 3/16” dacron or nylon line, stowing the loose end before leaving the dock.

13) Exercise during the off-season

Taking up a strenuous activity after a several-month layoff will cause aches, if not pains, in most people. A rowing machine does not provide the correct movement, and a paddling ergometer costs more than many kayaks.

Two resistance exercises will provide substantial muscle conditioning for paddling: The shoulder front raise and a modified row.

- Do the shoulder front raise with a dumbbell in one hand at a time, so that it also provides core strengthening. Stand with the opposite foot a little forward. Vary the arm position from straight ahead to 20 degrees inward. This strengthens the muscles that support the weight of the paddle, our outstretched arms, and any clothing on them.

- The modified row is most easily done at home with an exercise band that has handles, one of which has been secured to a strong structure. Grab and extend the band some, face it, place one foot back and use the arm on that side to simulate the “power” portion of a forward paddling stroke. Start slowly and gradually increase the resistance by moving back, aiming for 15 minutes with each arm.

A more consistent resistance force can be achieved by securely fastening two bands together to make an 8-9’ band. Alternatively, use a weight on a rope run through a pully secured to a tree branch or a garage beam. The simulation of paddling can be improved with the addition of a sturdy bench to sit on with the legs extended almost as high as the butt. This would be a good time to check paddling instruction videos for the preferred arm movements. An off-season conditioning routine should also include aerobic exercises of your choice and the stretches done during the paddling season. If you transport the craft on cartop and carry it to launch, another set of exercises that simulate those movements might be advisable.

Final thoughts

Why go to all this bother? Only if it allows you to paddle distances that otherwise would be too painful to enjoy. Why not just pop ibuprofen? Because it increases the risk of heart attacks and strokes, and because it can mask pain that is signaling body damage. I hope that some of these strategies will help you to paddle on.

-Gregg Jackson

Interested in chatting with Gregg and others about your own experience with minimizing pain? Join Gregg and others in the discussion below!

Did you know this article was a Paddler's Post submitted by one of your fellow paddlers?

Submit your own epic paddling tale, paddling lesson, or helpful tip and share with the community!

Related Articles

Stuff happens as we age, and it’s not all good. Darrell Foss, 75, one of my closest friends, has…

A not-so-funny thing happened this year. I turned 77. That's seventy-seven! Which is…

A short film produced (and paddled) by Jeremy T. Grant of the Timber Cross Film and Media. For more…

With very few exceptions, immersion in cold water is immediately life-threatening if you’re not wearing…