Kayak Paddles - Feathering and Ferrules

Yet another factor in choosing a paddle is whether you want a one-piece or a paddle that breaks down – a "two piece". There are two typical reasons for wanting a paddle that can be taken apart. The first is simply to make it easier to store when traveling or to stow on deck as a spare. The second reason, one that seems to be perpetually awash in opinions, is the ability to "feather" your paddle.

Most every beginner has been asked "Feathered or Unfeathered?" or "Do you right or left feather?" My deer-in-the-headlights expression to either question – at my first, ever kayak symposium back in the mid 80's – pretty much marked me as the consummate rookie on that beach.

An unfeathered paddle has both blades aligned along the same plane. Lay an unfeathered paddle on a flat surface and both blades will lie parallel to that surface. Rotate one of the powerfaces forward slightly, say to 30°, and you've now "feathered" the paddle. The feathered blade is offset from the working powerface blade and then rotated into position during the power stroke on that side of the kayak. Since either blade can be the dominant or starting entry blade when rotated properly, whichever hand you use to control the rotation is your dominant/control hand. Even a left-handed person might opt to utilize a Right feather.

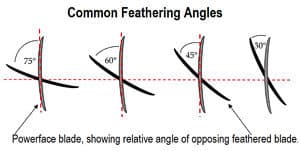

There are various degrees of rotation; some choose to go to the ultimate 90-degree right angle; others tend to range within angles between 30 and 60 degrees.

So, should you feather or not? A once highly contested and opinionated technique choice, the discussions about feathering vs. unfeathering have tempered over the years - from adamant rationalizing for one over the other into a matter of personal preference for either. That's not to say there doesn't remain strong feelings both ways as to which is the optimum orientation. As a prelude to that discussion, here's my biased opinion on the history of the feathered paddle.

Native paddlers never used a feathered paddle. Why? Derek Hutchinson once commented that it was merely that they just had never thought of it. Perhaps he was being a bit facetious. I respectfully disagree.

As kayaking evolved along the northern regions of the Pacific Rim of Asia, and later, North America, many paddling cultures didn’t even use a double bladed paddle. Many single paddles were very similar to canoe paddles and featured a long, relatively narrow pointed blade. Many of these paddlers, by the way, knelt in their kayaks – a position that might favor a single blade to execute a canoe-like stroke. Others did use the double kayak paddle so both were common through the ancient paddling world. And, look at Greenlander kayakers – no feathering in their paddles, either!

Limited paddle-making material was collected from driftwood washed ashore, including perhaps, timbers from shipwrecks. Many coastal villages at the mouths of rivers could often rely on trees that had been washed from along riverbanks in the interior of the continent to be carried downstream into the tidal flats.

Angling a blade beyond 20-30 degrees, cut from opposite ends of a timber would require a thicker/broader piece of wood to create a blade along a different plane angle from the other end. That's a significant expenditure of energy and time. This would have had to have been a one-piece feathered paddle at an unadjustable feather angle. That they would create a ferrule from materials at hand seems highly unlikely.

50 years of lightweight, maneuverable, high-performing kayaks.

Check out this interview with Tom Keane, Eddyline Kayaks Co-Owner, on their journey!

Natives developed the kayak, one of the most efficient human-powered vessels ever created, featuring technology, designs of crafts and gear that are still the foundation of form and lines used today. To presume they just hadn't thought of it in light of bifurcated bows, watertight seams and other innovations – balderdash!

Let's move ahead to the racing circuit, particularly the whitewater courses with their hanging gates and tight maneuvering runs. Wind resistance means loss of thousandths of a second in time; hitting a gate pole might cost a millisecond, too, or throw off timing. I'm not a whitewater guy but a common understanding is that feathering was born on whitewater courses.

Today the two most commonly acceptable reasons for feathering a paddle are:

- Decrease the affect of wind against the upstroke paddle by presenting an edge to the wind instead of a broad flat surface (as an unfeathered paddle would do)

- A more natural wrist movement and hence less wrist strain. Wrist strain, interestingly enough, is one of the strongest reasons why others choose not to feather.

Headwinds can affect an unfeathered paddle as the craft is directed into that oncoming resistance. Change the wind angle, to the side let's say, and that point becomes moot because with a feathered paddle, wind from varying degrees off port or starboard will produce a variety of similar affects on angled surfaces from those feathered blades as well. A side/quartering wind can sometimes push against the feathered blade in the upstroke position with enough force that it can cause a capsize if a paddler resists that push and clutches tightly onto the paddle. Experience soon teaches one to let go your upwind grip on your windward paddle and let the wind carry it to a point you can re-grip and swing it back into its proper position. The wind factor is valid but applies to both styles of blade alignment.

Greg Barton and Derek Hutchinson have both contended – and rightly so – that if your other paddling techniques are correct (posture, torso twist, etc.), you shouldn’t have any adverse wrist affects from using a feathered paddle.

Conversely, there are many who have tried both, who do suffer from wrist pain after prolong use of a feathered paddle, and have chosen to use an unfeathered paddle. It still all comes down to personal preference.

So, what if you do want to feather? What's the best two-piece system to get? What should one look for? Here are a few of the basic features to expect in a two-piece kayak paddle:

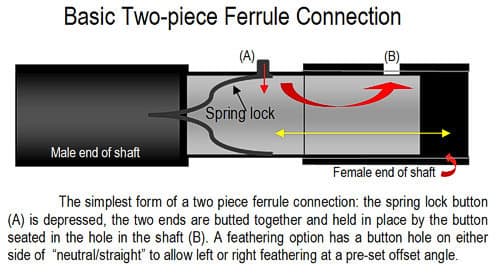

- Strength – You are buying a perfectly good, long, continuous cylinder of strong composite fiber that has been chopped completely in half! Strength has gone from 100% to zero! The connector used to re-join the two shaft pieces together is called a ferrule. The most basic ferrule unit is an insert within one side of the tube (the male end) that slides into the other end of the shaft (the female end) enabling the two ends to be butted firmly into one "continuous" shaft again. Typically a spring lock secures the two ends together with a button insert and then also enables you to depress that button to release the lock for breaking down the paddle.

- Durable – Right up there with being strong, the ferrule should be dependably durable – maintain its integrity through repeated adjustments - being banged around on deck, tossed about – general paddle abuse. If it cracks, jams or otherwise is compromised, there goes your fine-tuning and perhaps even more serious problems.

- Tight fitting – Whichever ferrule system you choose (and there are several as we'll show later), it must keep the joined sections from twisting, shifting or otherwise compromising the unity of the shaft. It's got to respond as if it were one solid piece. And you still have to be able to get it back apart. It must be tight, but well-fitted and seated.

- Simple/Intuitive – Most ferrules offer adjustments to change the feathering angle and/or to make slight changes in the overall length of the paddle. That calibration needs to be quick and simple and not require repeated scans at the instruction sheet or extensive sequences or steps. Easy-to-read calibration markings and even an audible click are used to help reassure a paddler that a proper adjustment has been made.

- High/Low/No Profile - Some paddlers prefer a totally flush shaft surface – no expansions or raised contours along it length. Others like a raised ring or collar to manipulate the ferrule angle. And there are some who don't mind all the locking/tightening/calibrating hardware out on the surface of the shaft. If you favor certain kayak rescues that might involve sliding or pressing your paddle along the deck of a boat, you might want to consider a ferrule system with few, if any, extruding/exterior components. That decision should be weighed by the extent of everyday use of the paddle vs. a hopefully rare or extreme need to perform a rescue procedure.

- Maintenance – Regardless of manufacturer's claims for any product, the more parts you have, the more pieces you have to maintain and run the risk of degradation or failure. The less grit and salty or dirty water that gets into components the better. Mechanism can certainly jam. Internal systems can collect and trap debris; external systems are constantly exposed. The best way to keep ferrule systems operating properly is to rinse them off with fresh water after a day’s use to remove salt, sand and grit as well as minute debris (dust, pollen) from within those mechanisms.

- Corrosion – Even stainless steel "stains". Metals tend to corrode over time; synthetics tend to stress fracture and may be susceptible to ultra-violent rays.

- Lubrication – Don't! Lubes can create a sticky surface for little microscopic nastiness to adhere its irritating, friction-causing self to surfaces and edges. Keeping your ferrules well rinsed is your best measure for keeping ferrules from locking up. If they do, you are better off contacting the manufacturer instead of trying any tricks you think will work.

There are three types of ferrule systems/configurations currently on the 2013 market - each with its own attributes:

Internal components – these offer some form of cinch locking mechanism within the shaft that enables the paddler to expand the shafts apart and using a twist/rotating motion, select a desired feather angle. Some even allow you to change the length of the paddle, too. These then lock into place for a secure fit. The setting can be viewed through a small opening in the shaft and an engaging button lies pretty much flush with the surface of the shaft.

Werner's Adjustable Smart-View Ferrule (shown above) and Lendal's Switchlok Ferrule (shown below) are two examples of this style.

Collars/Rings – These are low profile, exterior components encircling the ferrule and rotated to lock/unlock ferrules in selected positions. As in most all ferrules, calibrations are marked on the shaft for easy adjustment. These "swellings" on the shaft are formed to allow a smooth flow across their surface. Both angle and length adjustments options are possible.

Both H20 Performance Paddles' Fast Ferrule (shown above) and Aqua-Bound's Posi-Lok system (shown below) use this type of ferrule.

Lever action – These mechanisms rely on a lever to exert pressure on a ring or collar positioned at the ferrule. The lever enables the paddler to clamp down on the shaft and firmly grip it in position for solid angle/length adjustments. Levers can be adjusted to change or re-secure the tension exerted by the lever.

Epic's Length-Lock 2 (shown above) and AT Paddle's Adjustable Ferrule System (shown below) feature an external lever system.

Some ferrules allow you to select incremental feathering angles. Popular off-sets usually start at 30 degrees and increase in 15-degree increments up to 60 and sometimes 75, and much less common now, 90 degrees. Other ferrules enable you to lock in at any angle between 0 and upwards of 60, 75 or 90. In addition, some ferrules let you stretch or shrink the length of your paddle by several centimeters. Again there are incremental adjustments or full-range feather angle/lengthening options.

It's important to check out these systems and make your selection based in part on your paddling style and environment. So which one’s the best? That's up to you. How might your paddling style affect the type of ferrule you should consider? For example, do you tend to wear gloves? If so, which system will be the easiest to manipulate with those padded fingers – or cold hands? Do you paddle several kayaks using different lengths or styles of paddling? If you race, do you have an opportunity/need to change length or feather angle while on the course?

Hone your paddling skills with your best choice of feathered or unfeathered paddle checking hand positioning, torso twist, posture – all those critical components of proper paddling technique. Once your technique is correct and solid, check out the various options provided by today's manufacturers. You can learn all the details of each manufacturer's ferrule system on their websites - usually on the "Technology" link if not designated separately.

Selecting a paddle is as important as picking out the right kayak. If that first inexpensive paddle was a deal closer when you bought your kayak. Think seriously about an upgrade. The technology today is being incorporated by manufacturers to design and produce state-of-the-art paddles. A good kayak deserves an equally good paddle. Be safe; have fun out there.

Related Articles

Whenever you go paddling there's a certain amount of equipment that you have to think about before you…

Kayaks come in a variety of shapes and sizes and can be made from many different materials. Each design…

One of the most common, if not the most common, faux pas in paddle boarding is to hold and use…

Like a chef's knife, a climber's ice tool, or a woodsman's ax, a paddle can tell you a lot about its…