Battling Bugs!

A couple of hundred yards from the island, the huge fog-like smudge hanging just above the water’s surface slowly became more defined. A menacing mass of minute winged dots - thousands of tiny black flies - swarmed directly in front of our kayaks. The thought of swabbing ourselves in a wash of bug juice just to endure an overnight kayak campout was almost as discouraging as the thought of sucking in a mouthful of insect protein with every breath. We retreated, the bugs had won!

The war against annoying insects that bite, sting or otherwise bring discomfort to the outdoor enthusiast is usually carried out in multiple campaigns: the direct frontal assaults by an onslaught of warriors, the persistent and bold Kamikaze-like loner, and the infiltrator who sneaks behind enemy lines and attacks undercover.

To know your enemy is the first step in defeating them. Here are the most common critters we typically face throughout our outdoor paddling battlefield:

MOSQUITOS - The deadliest insect on Earth; linkd to over 100 disease-borne threats to humans. Among over 3,500 species worldwild, the Aedes vexes species includes the anopheles which carries malaria, West Nile, yellow fever, dingus, encephalitis and the dreaded Zika virus. ‘Skeeters can live up to five months, fly at 1.5 mph, and can detect carbon dioxide in breath up to 25 yards away;

TICKS - 850 species, some of which transmit Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever and Lyme Disease. Requiring high humidity to survive, ticks can also go several years without feeding! They don't jump or fly but rather hold onto their perch with their rear legs and grab onto prey with their longer front legs. Even the nearly invisible nymphal stage of the tick can bite and spread disease. They cycle through tiny mammals up through larger hosts;

CHIGGERS - Although there are no diseases associated in the United States, chiggers do spread typhus in some areas of the world. Bites are caused by tiny, nearly invisible mite larvae and can take up to four days to feed on a human host;

MIDGES - These are the most miniature of the "fly" species; we all know them as no-see-ums! Common mostly to coastal areas, swamps and marshes, they are known to attack in large numbers.

Collectively there are about one million species of "flies" worldwide including these annoying outdoor pests we've all encountered: black flies, deer flies, horse flies and even house flies. They can be found everywhere except the North and South Poles. Going by many names around the world, they are associated with Sand Fly Fever, RiverBlindness and other diseases.

BEES/WASPS - Inflictors of poisonous bites and stings including honey bees, African "Killer" bees, paper wasps, hornets and yellow jackets. Bees leave their stinger in the wound; wasps retain their stinger and can strike multiple times. While stings are painful, the danger lies in a possible fatal reaction for those allergic to the sting. Stings can cause muscle breakdown and swelling around throat or mouth causing restrictions to breathing. [NOTE: insect repellents are not effective against bees/wasps, etc.].

ANTS - More commonly found in the tropics, temperate zones and rain forests. Ants bite, Fire Ants sting! Chest pains, nausea, dizziness, shock and coma can result from the fire ant's sting. There are four species of fire ants in the United States; over 10,000 ant species worldwide.

SPIDERS - Most spiders we encounter are harmless. Two to avoid are the Black Widow and the Brown Recluse spiders. Black Widows are only about a 1/2 inch long and have a characteristic red hour glass shape underside on a black body. Their sting affects the nervous system causing chills, fever, abdominal pains and nausea.

The Brown Recluse can be up to 3/4" or more in size and come in a variety of brown tones. Its distinguishing mark is a violin shape on its upper surface. It's bite causes visible damage to the skin at the bite site. Pain might be delayed up to eight hour at which time it may be intense. It's not a pleasant wound, either - redness turns to a blister which breaks revealing a deep ulcer in the skin. Nasty stuff!

SCORPIONS - Only about 20 percent of the 2,000 species worldwide cause serious damage to humans. Of the 30 species of scorpions in the U.S., only one is harmful. Known as "bark" scorpions, they tend to hide in wood piles. Scorpions burrow in the soil and come out at night - they hide in cool, dark places. Most stings are caused when crushing or compressing the scorpion in a shoe or glove. (Best to sweep them aside, not press down upon them). Bites cause numbness, burning similar to a bee's sting, difficulty swallowing and blurry vision.

CATEPILLARS - Yup, even catepillars can "sting" - it's usually from the tiny hair- like spines along their often colorful bodies that creates an irritation. Those suffering from asthma, hay fever or other allergies should contact a doctor after an encounter.

The most frequent and widespread insects paddlers will encounter, while ashore and occasionally on the water, are mosquitos, flies and ticks. We can distance ourselves from the marauders or we can stand our ground and ward them off. In the latter scenario, the 7th Cavalry coming to the rescue is usually in the form of an insect repellent.

REPELLENT! REPELLENT? - Technically the chemicals (officially classified as a pesticide) we use to fight off insects actually mask or hide us from our attackers rather than "repel" the attacker from us. Repellents create a vapor barrier over our skin that masks the human attractant odors that mosquitos and other critters sense and use to zero in on us in the first place.

The human skin produces over 300 chemicals that mosquitos can 'smell'. A repellent hides those signature odors - scrambles those human scents - confusing the mosquito or other pest from realizing we are a source of blood they need to produce eggs for their own reproduction. They can also track us down from the CO2 in our breath, and the steroids and cholesterol secreted through our sweat glands.

Our presence is also betrayed by movement, heat, and lactic acid. Every person has a different set of scents, that along with other factors (clothes color is debatable) all affect how/why some are more prone to attracting mosquitoes than others.

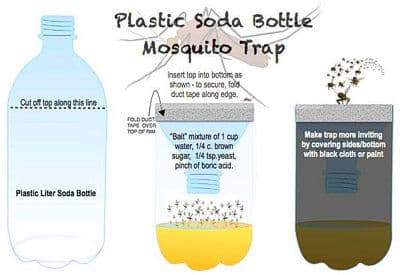

Repellents work by preventing, destroying, repelling or mitigating any pest. They can be applied to the skin, clip on pads or other mechanisms that disperse a repellent into the immediate vicinity, lanterns and other heating devices that dispense repellent, table top diffusers, candles and coils. While not a repellent, a baited insect trap can also be used against the war on insects.

The Environmental Protection Agency has several skin-applied active repellent ingredients registered in the United States. Here, briefly, is a description of each:

DEET - Developed by the U.S. Army in the late '40s to use against mosquitos, biting flies, fleas and small flying insects, it is probably the most traditionally wide-known bug juice chemical. It's been in the public domain since 1957. DEET is encapsulated in a polymer and gradually released over a period of time, typically between 8-12 hours. It's also a "plasticizer" meaning it can damage rubber, plastic. leather, vinyl, rayon, elastic and auto paint. (My first bottle of bug juice came in a little bottle from an Army surplus store - drops of it dissolved the painted surface of my dashboard - but it sure kept the notorious Minnesota 'skeeters and deer flies away!). Solutions that contain 30% DEET provide optimum effectiveness.

PICARIDIN - An extract in the pyrethroid family; synthetic chemicals that act like natural extracts from the chrysanthemum flower. Developed in Europe in 1998, it's an alternative to DEET, only better in many ways: doesn't damage fabric, surfaces or most materials. It's supposedly also works better against flies. It doesn't last quite as long (up to 8 hours). The optimum concentration in a repellent is a solution with 20% Picaridin listed.

OIL OF LEMON EUCALYPTUS - This is a synthesized plant oil, technically a chemical that is sometimes marketed as "plant based" or "botanical". It is not an "essential oil" nor is pure oil registered with the EPA.

Its optimum concentration in a repellent is 30% and is effective up to 6 hours. It may cause skin irritation in some users and should not be applied to children under 3 years of age.

IR3535 - Developed in Germany and used throughout Europe for over 20 years. No adverse affects; not harmful when ingested, inhaled or used on the skin. Effective up to 8 hours.

MINOR CONTENDERS - Lemon grass, citronella, cedar, geraniums and several other natural remedies have often been cited as natural plant oil repellents. While the EPA has deemed them safe, there is not much substantiation as to their effectiveness, especially over the long haul. Most need to be reapplied often (between 0.5 - 2 hours). It is not known whether natural oils are effective at repelling ticks.

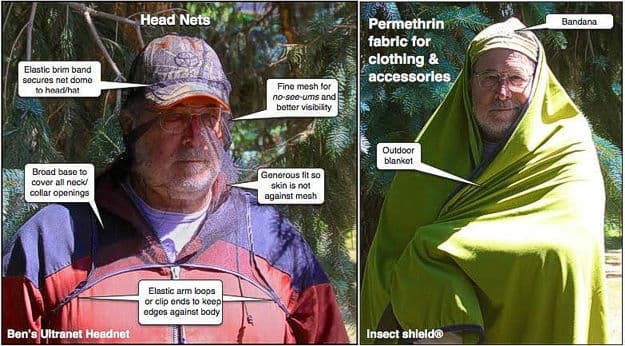

An alternative approach to repelling insects by applying chemicals over your skin in a coating is to impregnate your clothes with the repellent instead. One proprietary process bonds the repellent Permethrin directly to the fabric providing protection from insects pretty much throughout the life of the garment or accessory.

The bonding results in effective, odorless insect protection that survives undiminished for up to 70 washings. EPA tests show permethrin-treated clothing repels mosquitos, ants, ticks, flies, chiggers and midges - pretty much all the usual suspects you'll encounter on water or on shore.

Marketed as BugsAway®/Insect Shield® fabric with permethrin is used in a full range of clothing apparel (shirts, shorts, socks,) as well as accessories such as bandanas and camping blankets.

PHYSICAL CLOTHING BARRIERS - A headnet is usually standard issue in most backcountry paddling waters. Worn over the head, onto the shoulders and even full torso, a meshed hood can keep the mosquitos from biting (be sure mesh is not up against your skin or its purpose is defeated). Mesh clothing with elastic hems and clip lanyards stay in position better than cheap slip-overs that tend to shift. Loose fitting, fine mesh for visibility are two key features. Some netting may come with impregnated repellent as well.

Some backcountry/home remedies include:

- Using a smudge pot or smokey fire to ward off insects;

- Bruised leaves of catnip;

- Lemon balm, cedar;

- beer- baited insect traps;

- In an emergency - cover your exposed skin with thin layer of mud;

- Rubbing on apple cider vinegar.

With so many options, myriad products on the market and varying research into the range of effectiveness (do colors matter, should you eat more garlic, etc., etc., etc.) personal experimentation is probably the best way to learn what works for you outside the normal range of proven options.

However, there are several tips and cautions one should be aware of regarding the use of insect repellents. Here's a brief rundown on a few of them:

- Scrape the bee's stinger away with the edge of a credit card, finger nail or similar, do not squeeze sting area as that pushes more venom into the wound;

- Use tweezers to remove attached ticks by grasping tick's head at point of contact with skin and gently pull tick straight up, being careful to not leave any part of head in wound; do not squeeze tick's body;

- If victim of bee sting/bite is allergic, check to see if they have an auto injector and medication;

- Do not dry clean insect repellent fabric clothing;

- Do not apply insect repellents on infants younger than 2 years old;

- When sting is on fingers, hand, wrists - remove all jewelry as swelling may cause painful/damaging restrictions;

- Check concentrations of recommended repellents - high % concentrations are effective, but low concentrations are not;

- DEET, PICARIDIN, and OIL OF LEMON EUCALYPTUS are three proven effective insect repellent chemicals (Consumer Reports testing - specific repellents within these top brands with 100% effectiveness include: Ben’s/Sawyer/Repel/Natrapel/Off);

- Use just enough repellent to cover skin, heavier doses are not more effective;

- Don't use near food, fire, open skin wounds, eyes, mouth;

- Do not apply to children's hands for them to apply, rather rub on your own hands and apply repellent onto child;

- Mosquitos can bite through tight clothing;

- Light colored clothing makes it easier to spot ticks (certain colors attracting mosquitos is debatable).

***

General first aid/treatment for bites and stings is to remove the stinger if necessary, wash the area thoroughy with soap and water; apply cold compress to reduce pain and swelling, raise the sting to minimize swelling. Various ointments (those that contain hydrocortisone or other pain controllers) or creams (calamine lotion) can be applied. Tylenol, ibuprofen, Advil and others may help, too [NOTE: avoid ibuprofen for scorpion bites as it may cause other problems].

A simple home remedy is a paste made from baking soda and water. Most bite symptoms are gone in a day or two - the biggest concern will be allergic reactions. There are so many commercial insect repellents and devices, myriad home remedies coupled with such a broad range of factors affecting which method of insect repelling works for an equally diverse user group. Certain insect repellents are proven very effective, those chemicals have been incorporated into several different dispersal/delivery devices that one alone, or in combination, should help you ward off an invasion of insects no matter where your particular battle is raging.

Tom Watson is an avid sea kayaker and freelance writer. For more of Tom's paddling tips and gear reviews go to his website: www.wavetameradventures.comHe has written 2 books, "Kids Gone Paddlin" and "How to Think Like A Survivor" that are available on Amazon.com.

Related Articles

This question is from imsealin – they asked how long should a kayak be for sea kayaking, and can it be…

More times than not, the reason you aren't catching big fish is not because you aren't doing enough…

Ask any newcomer to the Allagash Wilderness Waterway or Boundary Waters Canoe Area what he or she fears…

Mention guns and canoe trips in the same breath and some folks are apt to go ballistic. Still, if you're…