The Practical Paddler: Part 12

What's in a name? Quite a lot, usually. Take Paddling.net, for instance. You probably don't visit the site to get the latest news about motocross racing or computer gaming. You're here because you're interested in canoeing or kayaking — or both. In other words, you like exploring the watery world under your own power, with paddle in hand. That doesn't mean you're not interested in anything else, of course. Canoeists and kayakers also watch birds, fish for trout and walleye, sail dinghies, take pictures, ride bicycles, and climb mountains. They may even go in for a sort of "intermodal recreation," combining two or more modes of avocational transport in a single journey. Intermodal transport is one of the Big Ideas now touted by policy wonks of the New Urbanist persuasion. Not being much of a policy wonk myself, however, I find the phrase a rather indigestible morsel. So I've taken to using the tag "amphibious trekking" to describe my multimodal approach to paddlesport, in which canoeing (or kayaking) trips usually incorporate cycling or hillwalking, as well.

The bottom line? On most paddling outings, I spend a lot of time on shanks' pony, and I don't confine these pedestrian interludes to the portage trail. With map and compass in hand (or at least in my pack), I climb nearby hills, walk the beds of streams too small to float a boat, geologize along river valleys and lakeshores, and wander away from marked paths to stalk the wild asparagus (or catch a glimpse of an elusive orchid). That means swapping my paddling footwear for something better adapted to the demands of yomping. And to my mind, when the going gets really tough, there's no substitute for real leather on my feet.

But this can pose problems for any similarly inclined peripatetic paddlers. Water and leather are natural enemies, and Canoe Country makes few concessions to would‑be amphibians, intermingling dry land, bog, beaver flow, and fen in a glorious, if somewhat sodden, patchwork. Venture off the beaten track, and you're sure to get your feet wet. Or at least you're sure to get your boots wet. Which helps to explain the astonishing proliferation of rubber (both traditional wellies and neoprene mukluks) and hybrid (Maine Hunting Shoes) boots, along with the recent reinvention of the overshoe (e.g., the NEOS Trekker), all of them claiming to combine reasonable comfort with at least some degree of waterproofing. Yet good as these alternatives are — and I've championed each of them at one time or another over the years — none can go the distance against leather when the route ahead grows steep and stony.

Which brings us back to water. Since water can be found just about everywhere in Canoe Country, you can't avoid putting your feet in it from time to time, and once leather gets wet — really wet — it takes a long while to dry. Trying to hurry the process along by setting your boots near the fire won't do the trick. At best, it's ineffective. At worst, if your impatience impels you to shove your boots too close to the coals, say, you'll reduce the leather to something resembling burnt toast, and just about as durable. The upshot? Open‑air drying is the paddler's only option once she leaves the put‑in behind. And if it's raining, with no letup in sight? Sorry, Charlene. You're doomed to spend the rest of your trip squelching miserably down the trail, with trench foot now a distinct possibility.

Is there an alternative to this soggy scenario? Yes. And it can be stated in that most enduring of old chestnuts:

An Ounce of Prevention Is Better Than a Pound of Cure

Though in this case, it should probably read, "Prevention is Your Only Option." The prescription, then, is simple: Use dubbin on leather footwear, and renew it often. But as simple as this prescription is, putting it into practice can be difficult. Devotees of leather footwear have never agreed on the best dubbin to use. And since I can claim no special expertise in the matter — despite having a brother who worked in a tannery — I will eschew argument. Instead, I'll just explain what I use. It works for me, and it might work for you. I make no other promises, and I offer no guarantees.

Enough throat‑clearing. My chosen dubbin is Atsko Sno‑Seal. It bills itself as the "original beeswax waterproofing," and for all I know, it is. That's not why I use it, though. I use it because it does a pretty good job of keeping my leather boots from becoming sodden during wet weather. Note that I do not say that it makes them waterproof. Nothing does that. Nothing that I've tried, anyway. But Sno‑Seal makes it possible for me to spend hours squishing across wet ground and still end the day with reasonably dry feet. I ask no more of any "waterproofing" compound.

Which explains why I Sno‑Seal my boots with meticulous regularity and an attention to ritual that is almost religious in character. And here's my Order of Service in summary form:

- I brush off any clinging dirt and …

- Remove the laces.

- Next, I warm the boots. (I use the sun. Or put them in my sleeping bag.)

- Now I scoop of a blob of Sno‑Seal with my fingers, …

- Spread it over the leather, and work it in well, giving seams and scuffed areas special attention.

- Then I set the boots aside in a warm place (sun or sleeping bag) to let the Sno‑Seal soak in.

- Finally, I treat any remaining dry spots, before …

- Wiping off the excess Sno‑Seal, and …

- Rethreading the laces.

Job done. Of course, nothing in life is really that simple, is it? Let's look at …

The Devils That Lurk in the Details

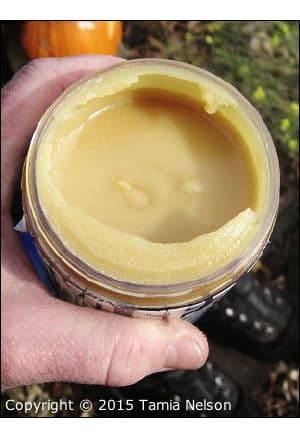

To begin with, here's a brand‑new jar of Sno‑Seal:

It has the appearance and consistency of peanut butter — albeit a rather etiolated peanut butter. (It doesn't smell anything like peanut butter, however. And I don't think I'd be tempted to put it on a bagel.) The Sno‑Seal of my youth was made of sterner stuff. It often had to be heated just to make it daubable. Today's Sno‑Seal has gotten soft. It's ready for use as is, right out of the jar.

But first things first. You won't want to dubbin your boots till you've dried them. You'll also want to get them as clean as possible. An old toothbrush is the perfect tool for this, though I've used everything from my fingers to a wadded‑up bandana. Wet or muddy boots are nearly impossible to clean, by the way. Wait till they're completely dry before wielding your brush or bandana. The job will be much easier then.

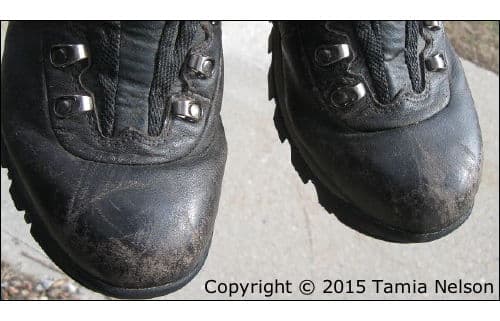

Next, remove the laces. This step is self‑explanatory, I hope. Take the opportunity to inspect your boots for cuts or worn stitching, too:

Notice the number of seams in the uppers of my boots. Back in the day, good‑quality hiking and climbing boots had uppers made from a single piece of leather. (Most also boasted a gusseted tongue and a heel counter-cum-pull‑on loop.) Such boots are still available, but their cost puts them beyond the reach of impecunious hacks. I buy what I can afford, and that means my boots are pieced together from smaller scraps of leather. This isn't a recipe for longevity, but that matters less than it might once have done, since few modern boots can be resoled — and anyway, shoe repair shops have all but vanished from the rural landscape. We're each of us consumers now, after all, and the health of the economy is measured by its throughput. Repairing things is so, well, yesterday. In fact, tossing stuff out before its time is now both a moral imperative and an obligation of citizenship.

But I digress. My boots are the best I can afford. And keeping the uppers well dubbined will help ensure that they hold together long enough for me to get as much wear as possible from the soles. That's the most I can hope for. So each seam needs special attention every time I Sno‑Seal the uppers — as do these badly scuffed toes:

Once I've brushed off all the loose dirt, the next step is easy: I put my boots someplace warm.Warm, mind. Not hot. Whatever else you do, ignore well‑meaning advice to put your boots in the oven to "help the Sno‑Seal soak in." Unless you fancy roasted boot for dinner, that is. The photos I've used to illustrate this article were taken last fall, when I was able to work outside. This isn't really a necessity from an 'elf 'n' safety standpoint. Sno‑Seal is pretty innocuous stuff, and I could have done the job in the kitchen, if I'd wanted to. But the day was pleasant, and I took full advantage of the warm sun and cloudless sky, placing my boots on a gravel apron and letting Sol do his work.

Then, once the boots felt warm to the touch, I gloved up, drawing on my stock of nitrile surgical gloves, kept handy for messy chores like cleaning bicycle chains, fiberglassing boats, and, yes, greasing boots. Strictly speaking, this precaution was also unnecessary. But Sno‑Seal is tenacious stuff — a good thing in a dubbin — and I didn't fancy a Sno‑Seal garnish to my dinner. Now it was just a matter of scooping out a teaspoon‑sized blob of dubbin from the jar and rubbing it onto the upper of the first boot, including the tongue and collar. I gave the numerous seams a little extra attention, into the bargain. And as soon as I'd finished with one boot, I restored it to its place in the sun, then clawed another teaspoon‑sized gob of Sno‑Seal out of the jar and turned my attention to its mate.

The job went quickly, and after letting both boots bask for a few minutes more, I inspected my handiwork, searching for places that still seemed a bit dry. I found a few. They got a second dressing of Sno‑Seal. And that was that. I often overestimate how much dubbin I'll need at some stage in the proceedings, necessitating a quick wipe with a rag to mop up the surplus. (Leaving gobs of excess Sno‑Seal on boots simply attracts and holds dirt.) But this time around I judged the amounts exactly right. There was nothing to mop up. All that remained was for me to don my boots and take a hike down to The River to see what I could see. Which is exactly what I did.

Leather boots used to be a common sight in the backcountry. But synthetic fabrics and rubber have now displaced leather from its former pedal preeminence. No matter. I find that nothing beats leather for off‑trail rambles in rough country. That said, leather won't serve you well if you neglect it. Fortunately, though, the care and feeding of leather boots is pretty straightforward. It's mostly a matter of daubing on dubbin from time to time. And as you can see from the foregoing, this is a pretty small price to pay for dry feet.

Related Articles

In this video, the team at Austin Kayak show you how to rebuild your keel if you have created a hole…

In this video, Ken Whiting of PaddleTV is talking about how to care for the latex gaskets on your dry…

What is the main difference between a dry suit and a semi-dry suit? Why is there's such a big difference…

I remember the anticipation of the spring thaw when I could finally get out on the water again after a…