T-Recovery

The T-recovery is one of many assisted recoveries where the water is drained from the flooded kayak before the paddler re-enters their kayak. The T-recovery is only effective if there is a bulkhead behind the seat and if the assisting kayaker lifts the bow while the kayak is overturned. The water in the kayak will drain out due to the bulkhead keeping the water from continuing from the cockpit into the stern of the boat. If there were no rear bulkhead, then a T would have to become a TX if you wanted to drain the water. A TX recovery drains water from the entire kayak when there are no bulkheads or if you start your recovery by lifting the stern first (See USK article, "TX-Recovery").

The "T" and all of the other "Alphabet Recoveries" (a phrase I once heard John Dowd use in a lecture) get their name by the configuration of the kayaks as seen from above. They are all used for draining water out of the capsized kayak. If you did not have a pump with you, if your pump were lost or if it malfunctioned, then draining the water would be your most viable option for getting water out of your kayak. Therefore, knowing the T-recovery can provide you additional options.

In this day of rear bulkheads being the norm, I can say the T-recovery is my assisted recovery of choice. I can do a T-drain on a kayak very quickly. Once you get good at T-recoveries, you can have your partner back into a drained kayak quickly. The average time it takes me to drain a kayak is 10 to 15 seconds, which is much shorter than the average pumping time.

T-recoveries are not recommended:

If your partner is in cold water and they are not dressed properly for immersion If you are not strong enough to lift the kayak to drain the water

If the swamped kayak is too heavy for one person to lift, then you could have another paddler help with lifting on the T-drain (See USK article, "Utilizing The Group").

As in all recoveries, the paddler that wet exits needs to keep in contact with their paddle and kayak at all times. I teach my students not to give up their paddle until they are ready for their re-entry. Then they hand it off to the assisting kayaker. As a side note, if you paddle a Sit-on-Top (SOT) you can perform a T-recovery on a closed deck boat. The big difference is the bow will actually be on your lap instead of resting on a cockpit coaming.

On a historical note, the TX recovery was the recommended two-person assisted recovery when there were no bulkheads in kayaks. The T-recovery was not an option for sea kayakers until rear bulkheads were installed. Bulkheads could not be installed until watertight hatches were developed. This is another example of technology providing more options and improving safety in the sport of sea kayaking.

I teach my students to aim for the bow of the kayak they are going to assist. Remember, lifting the stern leaves too much water in the cockpit, so a TX drain would be needed and the TX method is much more time consuming and requires more energy. You can identify the bow if there is a rudder or a skeg on the stern. When you get closer to the kayak you can also look for the screws that secure the foot tracks in place. They will be closer to the bow. If you end up by the stern you can easily walk the kayak to the bow before draining the water (See USK article, "Walking A Kayak").

When I get to the bow I quickly store my paddle under a bungee cord (on the opposite side of the kayak in need) so I have hands free operation. As a side note, when you are in the T position the flooded kayak can be a great source of support for you, if it has adequate floatation and if you have a solid grip on the kayak. Once you get to the bow, you need to break the seal created between the cockpit and the water in order to lift the bow so you can get the bow over your cockpit or lap. There are three primary ways of accomplishing this goal.

The traditional method (stern drop) uses the weight of the paddler in the water to raise the bow by jumping on the stern of the overturned kayak. This action not only breaks the cockpit seal it also lifts the bow so it can be directed onto the lap of the assisting boater. This requires less effort on the part of the assisting boater, but requires communication and orchestration between the two paddlers.

There are two other ways to break the cockpit seal that are mentioned later in this article. Regardless of the method you use to break the cockpit seal, the T-recovery is completed the same way.

Once the bow is lifted let the water drain out of the cockpit of the overturned kayak. Keeping the bow up in the air when you turn the kayak upright will help prevent the cockpit from scooping water.

When the water is out, turn the kayak upright. Then you slide the kayak back into the water and turn yourself into the orientation you prefer for stabilizing the kayak so the paddler in the water can get back into his or her kayak.

I prefer a bow to stern orientation, because I have more options of helping my partner when they are climbing back into their kayak. This method also keeps me out of their way. I am not blocking their cockpit during their re-entry process. The bow to stern stabilizing method also allows me to watch my partner while they re-enter.

When your partner is climbing onto their kayak, you can use the paddles as a paddle bridge to help you support the kayak or put the paddles under bungee cords to have them out of the way.

I mentioned earlier, that I train my students to hold onto their paddle while they are in the water and not to give up their paddle until they are ready to climb on to their kayak.

The goal of the assisting boater is to keep the kayak stabilized regardless of the re-entry method your partner chooses. Remember; do not let go of your partner's kayak until they tell you to do so.

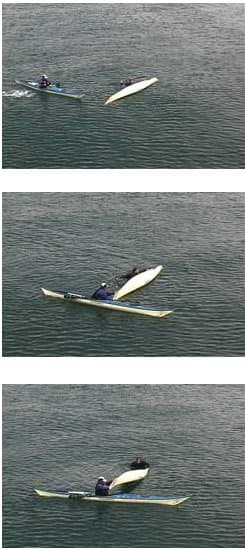

Instead of using the stern drop to break the seal of the overturned kayak I prefer to use a method I call the bow hook. Your goal is to break the seal without help from your partner.

As many have learned (the hard/wet way), if you just try to lift the bow you can pull yourself over. I have found great stability from the overturned kayak. I actually lean on it and then put my kayak on edge so I can put my cockpit coaming under the end of the overturned kayak as I lift that same kayak. When the end of the kayak is over my coaming, I use a little hip flick to raise the nose up (my cockpit coaming is the lever), which breaks the cockpit seal of the overturned kayak.

Then I continue to lift the bow in order to drain the water as described above. I like this method best because it takes less time and orchestration.

This method can be used to hook either end of the kayak. The pictures here are showing the hook being used on the stern of a kayak that has a drop skeg. In this particular case a TX would have to be used to get the water out. If this method were applied to the bow then a T-drain would be sufficient. Doing a stern hook, when a rudder is present, can get complicated and somewhat dangerous. I strongly suggest you avoid it or else watch those fingers.

An easier method of breaking the seal and getting the bow over your coaming is using the bow slide. I learned this one from Derek Hutchinson. When you get to the kayak, your first goal is to get the kayak flipped right side up. You can try to do it from the bow by yourself or have the paddler in the water flip it upright while they are at the cockpit. A more time efficient way is to shout out, as you approach, to the paddler in the water to right their kayak before you get to them. The person in the water has better leverage to flip the kayak upright.

This method takes advantage of the bow design to minimize your efforts. With an upright kayak you can use the slope of the bow to slide the kayak up onto your kayak (or lap with a SOT). If deck lines are present the job is even easier (another good reason for deck lines. If you don't have them go out and put them on. The life you save will be your own.

Once the bow is over your coaming let the kayak tilt to the side and the water will begin to drain. I prefer to tilt the kayak (cockpit opening facing my stern) so I can see the water coming out of the cockpit. I continue to lift the bow until the water is out. As before, once the water is out I continue with the rest of the recovery.

A word of caution if you have a kayak without bulkheads and without float bags (which should never be the case), because when you turn the swamped kayak upright the remaining air trapped in the kayak may escape which could send the flooded kayak into Neptune's junkyard. If you choose to use this method on such a poorly outfitted kayak, it would be a good idea to clip a towrope on the end grab loop before you turned the kayak upright in case the kayak were to sink.

Regardless of the recovery method you choose to use, the kayaker in the water has a responsibility to be proactive and communicative as the assisting paddler is approaching. The swimmer can direct the assisting boater towards the bow. Where the swimmer positions him or herself is dependent upon the method the assisting paddler will use. Another benefit of communicating with each other as the assisting paddler approaches, it shows that you are not panicking.

As an example, if I choose to use the stern drop method for breaking the cockpit seal I will swim to the stern as the assisting boat approaches. My goal is to minimize my exposure time. All too often the person in the water just floats around doing nothing. Just waiting for help to arrive without acting is not in your best interest. Sometimes just pulling or pushing a kayak toward your partner will save thirty seconds of maneuvering on their part.

If I plan to use the bow hook or bow slide I shout out to my partner to get to their cockpit and stay there while I do my thing. If it is a bow slide I also tell them to right the kayak before I get there.

As I mentioned earlier, I use the T-recovery as my primary assisted recovery method. I have practiced it so I can do it very quickly and without any help from my partner. After all, the paddler in the water may be hypothermic and beyond helping me. If that is the case, your next difficulty is getting them back into their kayak. If the paddler in the water is too far-gone, this T-Recovery will not be the recovery of choice.

Pictures seen above were taken from the USK video Capsize Recoveries & Rescue Procedures

Wayne Horodowich, founder of The University of Sea Kayaking (USK), writes monthly articles for the USK web site. In addition, Wayne has produced the popular "In Depth" Instructional Video Series for Sea Kayaking.

Related Articles

Even though they are flipping over, missing their gates and failing their maneuvers, they still look…

Last month we discussed how to detect and patch (not "repair") a leak on a typical roto-molded kayak…

A kayaker should have a number of recovery methods to choose from in their bag of skills. I feel the…

There are two ways of swimming through a rapid. You can swim defensively or offensively. Defensive…