Ice Paddling

By Tom Watson

I suppose for paddlers living where the ponds never freeze over in winter, kayaking in ice conditions is an experience few have even considered, let alone experienced. For those whose kayaking learning curve arches through the more northern regions of the paddling world, pushing that curve into the heart of winter is an annual seasonal challenge.

Inland water paddlers in the higher latitudes of the continental US can enjoy open water on some lakes and rivers throughout the entire winter. Others may push the envelope by squeezing in a paddle before the ultimate freeze-over. For those whose coastlines are dotted with tidal glaciers, paddling in ice is a year-round cautionary consideration that takes on seasonal characteristics and challenges.

Freshwater Ice Paddling

First and foremost, safety is the main concern when paddling. Very cold water and weather heighten a paddler's awareness and preparation. I urge you to check out Jeffery Lee's article "Safe Cold-Water Kayaking" for tips and techniques to learn and practice for cold water/weather paddling. Beyond those precautions and preparations, one's concerns about paddling with ice can focus on the types of icy situations typically encountered during a winter canoe or kayak outing.

Open water in the winter is obviously dependent upon the severity of the weather at the onset of that season. The areas around the mouths of streams/rivers that flow into larger bodies of water often stay open longer than the expansive surfaces of lake water.

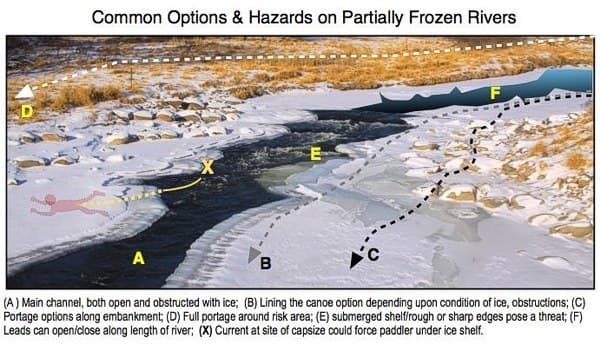

Depending upon the intensity and duration of freezing weather, some open water remains even during the coldest spells. Other times there are open passages along a stretch of river ice or throughout an otherwise ice-covered lake. Called "leads", these openings through the ice enable a paddler to explore throughout the range of unfrozen water.

Sometimes a paddler is challenged to press ahead through weak/thin ice, either to re-enter open water or to the point where further advancement is thwarted by ice too thick to easily break. If, however, that isthmus of ice is narrow enough, a bold kayaker with a bomb-proof hull might decide to slide up onto the ice and use his/her paddle to pole across this 'hard' water. I have found that fiberglass blades cut nicely into softer or rougher icy surfaces but slip miserably if the surface is too slick and hard. Putting too much weight onto the paddle against ice that doesn't budge is a good way to break your shaft, too. A prudent "ice paddler" should know when to yield to the ice.

A serious concern about lake and river paddling involves a capsize - and for more reasons than exposure to life-robbing cold water. A capsize near the edge of an ice surface can be fatal. Not only is there immediate danger from exposure to cold water, currents or wind can force a paddler back under the edge of the ice - with no immediate openings for escape or rescue.

Ice can also do nasty things to your hull. Inflatables would seldom resist the slashing of sharp edges; gelcoats are ground away in small flecks as ice chisels at the bow. Plastic hulls, while perhaps the best material to face up to the challenge of playing ice-breaker, will probably suffer a bow combed with scratches that will take its toll eventually, too.

'Blue Water' Ice

Coastal ice formations in the farther northern/southern hemispheres are typically the result of extremely cold weather and tidal glaciers. Yes, salt water does freeze - albeit at lower temperatures. Wind spraying sea mist onto a cold kayak in freezing weather can build up a deadly glaze in minutes. That additional weight can cause a kayak's center of gravity/balance to change in a hurry.

Ice can be formed into myriad shapes and conditions by the wind and tides. Each type of ice creates different dynamics of surface movement and challenges to the paddler. Here are a few of the terms used to describe the many different types of sea ice:

Frazil ice: fine spikes or plates of ice suspended in water Grease ice: crystals form a soupy layer on the surface Brash ice: floating ice comprised of small fragments of wreckage from other ice forms, etc. Bergy bits: large piece of floating glacier ice between 3'-16' above water surface Ice cake: smaller flat pieces of sea ice Pancake Ice: circular flat ice with upturned edge due to repeated wind-blown/current collisions. Pancake ice can form from a variety of ice conditions. Fast Ice: Ice that forms and remains along a coast; fast ice thicker than 7' is called an ice shelf. Floe: Flat, isolated section of ice at least 65' across. A "giant" floe is ice extending more than 5.5 nautical miles. Lead: A passageway or fracture through the ice that is navigable to a surface vessel.

Several of these characteristic ice forms can occur within the same section of water. A prudent paddler should be aware of the individual and combined dangers these forms present.

Tides and Glaciers

Knowing what the tides are doing is a critical aspect of blue water paddling. Incoming tides push the ices floating out away from shore back in towards or right up to the beach, sometimes completely barricading the shoreline from open water. Conversely, a shore that is stacked high with deposited ice can be washed clean during a receding tide. Checking the tide tables when planning a beach landing or launch can help you estimate ice flows and obstructions accordingly.

Paddling up towards the face of a glacier is an exhilarating experience. Not only is that massive wall of ice - speckled with debris and incredible oxygen-depleted blues - a spectacular sight, the grumbling, trickling, moaning sounds from within its face are equally mesmerizing. The beauty belies the beast within.

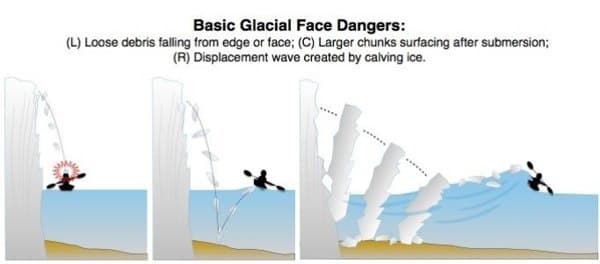

Glaciers, as motionless as they appear, are alive; constantly in micro-motion. The face of most glaciers is in a constant state of disintegration. Whether it's the explosive calving off of massive chunks of ice weighing hundreds of tons or small fist-size chunks tumbling down from the edge, a glacier's face can be one of death. Several kayakers' have been killed or severely injured when they've approached too closely to a glacier's edge and were subsequently hit or capsized by ice breaking off its icy face.

Large chunks of ice can bob up from a forceful submersion and huge walls of ice can create a powerful wave surge roaring out from the glacier face.

Here are some general safety tips regarding winter paddling:

- Neoprene freezes when wet

- Consider decking for canoeing in winter to keep paddlers warm

- Consider foam knee pads to insulate against cold hull/water

- Clear ice is hard, more safe; "black" ice is soft, less safe

- Use "Tick-Tock" test to help determine ice quality. Tap surface with hard object: "Tick" sound means hard "Tock" sound means weak ice, air pockets, etc.

- Leads can close up and trap your kayak in a frozen, icy grip - be aware of ever-changing conditions

- Follow smart cold-weather paddling clothing procedures

- Whenever traversing/stepping onto ice, carry Ice Awls with you

- ALWAYS develop and leave a Float Plan.

Facing icy waters extends the paddling season to a full year's worth of opportunity to enjoy nature in all of her moods. Being aware of the dangers and having an action plan is paramount to safe winter paddling. Proper clothing, on-water practice of rescues techniques, and an awareness of our surrounding environment throughout it's seasonal changes are critical for the safety and enjoyment for ice paddling on all levels. Be safe; have fun out there.

Tom Watson is an avid sea kayaker and freelance writer. For more of Tom's paddling tips and gear reviews go to his website: www.wavetameradventures.comHe has written 2 books, "Kids Gone Paddlin" and "How to Think Like A Survivor"that are available on Amazon.com.

Related Articles

Flexibility is always a good topic of discussion when it comes to kayaking. Depending on our style of…

Kayak Catfish does some trolling with crappie magnets to catch some catfish bait.

How many of you have ever heard that paddle craft (vessels under oars according to the Navigation Rules)…

More times than not, the reason you aren't catching big fish is not because you aren't doing enough…