Getting to Know Outdoor Fabrics

Polytetrafluoroethylene, "hydrophilic monolithic laminates", oleophobic or perhaps even WVTRs – enough to make you run to your college bio-chem textbook, right? And you might want to latch onto a dictionary of marketing catch phrase labeling while you are at it.

Sounds like a strange intro to an article on outdoor fabric, doesn't it? Not so today, especially in a world of hybrid synthetic fibers and micro-layering where products featuring überfabrics and secret proprietary processes with differences measured in microns try to out-perform rivals while vying for the outdoor consumer's dollar.

Through dozens of years playing on land and on water, I've learned about what to wear and not: "There's no such thing as bad weather – just bad clothing!" was a common landlubber's warning while "Dress for the water, not for the air" was an oft-repeated safety tip, especially on balmy days when preparing to paddle out onto the frigid waters of the north Pacific. The classic verbal red flag in both environments, however, was: "Cotton Kills!"

So, what is the story about fabrics used for clothing and other gear in our moist, cold and often take-no-prisoners outdoor environment?

BASIC REQUIREMENTS

Our primary, life-sustaining "fabric" is our skin. It's the body's largest organ; it protects us from external intrusions as well as helps regulate several internal processes. One very vital process is heat regulation. We need to maintain a core temperature of around 98°F/34°C – you know the numbers. When we get too hot, we start to sweat – our body's way of helping us cool down. Cool down too much and we become hypothermic – a major killer.

We lose heat through radiation, convection (wind), conduction (cold ground), evaporation and respiration. Moisture against or near your skin (directly or from absorbing layers) can conduct heat away and excessive moisture may not be evaporated or carried away fast enough to prevent core cooling. It can also mask the fact that you are still cooling since sweating is a true indicator: "Hmmm, No sweat! Must no longer be cooling!" That could be a fatal assumption.

A qualified ideal solution to staying dry and well ventilated in the rain would be to stand naked under a broad umbrella. The dome overhead keeps you dry (heat loss or wind notwithstanding) and your naked body ensures total ventilating of your skin. There are obvious and severe limitations to this particular solution. Hence we have artificial skins in the form of fabrics that attempt to approach that same level of completeness while providing mobility and other obvious benefits.

TAHE 10'6 & 11'6 SUP-YAK Inflatables

2-in-1 Kayak & Paddle Board complete packages for single or tandem use.

IN THE BEGINNING – NATURAL FIBERS-

Hemp is probably the oldest fiber known to Man. Akin to wearing burlap, it most likely became a valuable necessity when animal hides were scarce or as easier processing and applications were discovered.

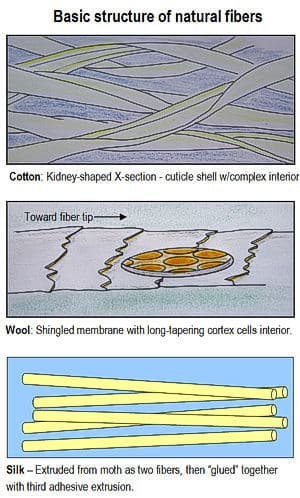

The legend of silk is that a Chinese Emperor's bride discovered the fiber when a cocoon from a moth fell into her hot tea and unraveled in a long string of thin, but strong strands. The natural process of producing silk involves two extruded fiber sources merging just outside the insect's mouth and being bonded together by a third extrusion of adhesive. Silk's strength and softness makes it a fabulous material while it's great absorption capacity for water (can absorb up to 30% of its weight without feeling wet) adds both pros and cons in certain situations.

Cotton may, indeed "kill" because it absorbs so much water and therefore loses most of its insulating qualities, and also makes the garment incredibly heavy. Cotton is mostly cellulose; the fibers are a complex structure with many electronegative oxygen atoms. These natural bond with electropositive hydrogen atoms in the air. So the oxygen in the cotton and the hydrogen in the water combine (like a water magnet) and – voila- you've got some seriously wet cotton! Wearing cotton jeans during a capsize adds many pounds of excess weight and will start cooling you down as soon as you (hopefully!) re-enter your boat. If you don't recover in time – cotton's reputation for fatality is validated.

However, it does work well to cool one down as it allows air to flow through the fabric and also protects against UV rays. When combined with certain synthetic fabrics or treatments, many of its negative properties are lessened or mitigated.

Wool is perhaps the best-known and still popular outdoor natural fiber in use today. A close look at a single wool fiber reveals a series of shingle-like overlaps of cuticle cells made up of proteins and waxy lipids forming an outer layer over an inner, cortex core of long-tapering cells. Different wools have different properties of appearance and feel and are used in applications that best utilize those characteristics. One of wool's most noted features is the fact that it provides warmth even when wet. It's waxy exterior makes it repel water while allowing vapor to pass through (a term called breathability). These attributes are also primary selling points with most of the synthetic fibers used in outdoor clothing on the market today.

Merino wool, from Australia, is at the acme of the wool fabric world when it comes to its use in outdoor garments. Beyond it’s natural properties of thermal-regulating, moisture-wicking, antimicrobial, insulating, water-repellent, breathable, durable and biodegradable, merino's fine fibers make it especially soft and comfortable, too. To make this super wool even better, it is blended with a variety of synthetic fibers that combine the attributes of both to make the merino products even stronger, more durable and so on.

THE AGE OF SYNTHETICS

Most modern synthetic fibers are compounds that are combined to form layers that are laminated and made into compounded fabrics. They are most often petro-chemical polymers (from Greek: ,polus=many, much and meros=parts) - a chemical compound or mixture of compounds made up of repeating molecular units. Some synthetics are made from animal or plant bases (rayon is made from cellulose fibers) as well.

The process for forming these fibers is very similar to that used by the moth to make silk. Fiber-forming materials (polymerized petro-chemicals bonded in long molecules joined by adjacent carbon atom) are forced into the air through small openings forming threads. The variety of fibers created share many common characteristics that make them especially suited for outdoor garments including:

- Heat-sensitive

- Resistant to insects, fungi, etc.

- Low moisture absorbency

- Density/specific gravity

- Piling

And because they are usually cheaper to produce and process – economics plays a big role in the outdoor clothing business! One of the most serious drawbacks of synthetic fibers is that while they are usually flame resistant, they will melt. This makes they unsuited for many commercial uses where intense heat may occur – and why you get those melted pits in your fleece and outer shells by sitting downwind of a sparking campfire. Nearly 50% of all fiber use is synthetic with nylon (a thermoplastic - "synthetic silk"), polyester, acrylic and polyolefin making up nearly 98% of that use.

Most of the polymers used in outdoor gear are in the form of films that coat or are laminated to other poly fabric (and sometimes natural ones as well). Let's look at some of the base synthetics and other materials used alone or compounded in outdoor gear:

Polypropylene films – a thermoplastic polymer resin consisting of branched units derived from propane and joined with methane. It is very similar to polyethylene – the "plastic" in rotomold kayaks!

Polyurethane films – Often listed as “PU” in fabric/application descriptions, it is perhaps the magic ingredient in most waterproof/breathable fabric. It is continually being improved upon and altered as a protective layer on many new fabrics (as it is was initially and still being used as the protecting layer in Gore-Tex™, and other new fabric innovations). PU layers are used to make garments lighter and stretchable, important aspects of fit and comfort in clothing. The are also more impact resistant than other polys (knee areas, hard contact from a fall, etc.).

Polyester films – another polymer but not as performance capable as other "polys" – yet! One advantage it has is that it is recyclable if bonded to another polyester film.

PTFE - Our opening sentence chemical tongue-twister, Polytetrafluoroethylene! It's a fluorocarbon-based film whose use is widely known as Teflon™. In one of its many hybrid forms it is the definite layer used in the production of Gore-Tex™ and other developing technology entries into the marketplace. The marketing side of outdoor wear has come up with dozens of buzz-words to label their proprietary fabrics, most of which are made from these base polymers using ever-developing attributes, refinements and other secret processes.

Some of the most notable and familiar hybrid fabrics used in clothing and gear include:

- Cordura – We all know the toughness of Cordura (used in clothing and gear, including PFDs and other water products. It offers the durability of nylon with the comfort of cotton: it’s strong, lightweight, highly abrasion resistant, high tensile and tear strengths.

- Neoprene – Easier to say than polychloroprene, it is in a family of synthetic rubbers that are polymers of cholorprene that are ingredients in the production of other materials. When used in diving and insulated garments, the neoprene rubber foamed by impregnating it with nitrogen gas to form tiny, insulating spaces also makes the final garment buoyant. Spandex™ (a polyurethane based co-polymer) whose marketing name is an anagram for "expands" is added to give the neoprene suits even more stretch for fit and comfort.

- "Fleece" – The synthetic kind, is an insulating, soft napped synthetic fabric that is polyethylene or other synthetic fiber based. It has many of the finest wool's qualities at less weight.

This has been a skeletal overview of the most common base fabrics and fibers used in today's outdoor garments and gear. The use of these materials in laminates and coats as well as the ever-growing technology on improvements and refinements means a whole new level of clothing options for today's outdoor enthusiast.

Next time we'll take a look at "Gore-Tex & Beyond" and also address the topics of: Water Proofing/Breathability and Tips on the maintenance of these garments.

Tom Watson is an avid sea kayaker and freelance writer. For more of Tom's paddling tips and gear reviews go to his website: www.wavetameradventures.comHe has written 2 books, "Kids Gone Paddlin" and "How to Think Like A Survivor" that are available on Amazon.com.

Related Articles

Like kids in a candy shop, we geek out every year at Canoecopia in Madison, WI. One of the few chances…

I like wearing wool. I always have. Some may think it's because I'm too cheap to buy some of the…

"The tents weren't all that great, and I often slept under a canoe and would wrap my head in a towel to…

Hi, Jeff Little here. I'm the regional Pro Staff director for the Wilderness Systems Fishing…