Crisis On The Rio Grande River

Once upon a time, I believed that the best canoeing rivers were in Canada and Alaska. Then, about 15 years ago, my friend, Larry Rice suggested we canoe the Rio Grande River—a remote, spectacular desert river in Big Bend National Park that forms the border with the U.S. and Mexico. My initial response was, “Nah, I’ve seen enough John Wayne movies to know that river is boring!"

Wrong! The RioG is actually a mountain river for part of its flow, passing between the Chisos Mountains in Texas and the Sierra Madre Oriental in Mexico. The 220 mile canoeable section that borders Big Bend National Park is spectacular and remote. Crash your canoe in one of the many rapids here (many people have!) and it’s a long walk out on barely identifiable trails through a dry desert where everything stings, cuts or burns.

The Rio Grande is no sissy river. Best come with reliable paddle skills!

I’ve canoed the river four times (2011, 2016, 2017, 2019). On runs before 2019, water flows ranged from a barely runnable 150 cfs (cubic feet per second) to 550 cfs, a low but ideal level for open canoes. On this, our most recent trip, we were a group of four in two solo canoes and one tandem. We launched at Lajitas, Texas on November 4, 2019. The flow rate was 550 cfs and the sun was shining—perfect!

Past Rio Grande trips have always been in February, and typically we barely saw a soul—just free-ranging horses and cows, wild pig-like javelinas, great blue herons, soaring hawks, and road-runners, plus, on occasion, a few congenial Mexican vaqueros (cowboys) on horseback, searching for wayward livestock. But now we were running into boating parties practically every day. Among them were three “river rangers” (two men and one woman) on patrol. We paused to chat. They were friendly and helpful, river-knowledgeable and equipped for emergencies—and most importantly, dedicated to making the river experience enjoyable for all. Note that just three law-enforcement personnel are responsible for patrolling the 118 miles of river that border Big Bend National Park—an impossible task for so small a crew. My hat is off to them.

On our first day, not long after we made camp at the entrance of Santa Elena Canyon, the first of two major canyons we would be traversing, we encountered a party of two canoes—a 40 year old man paddling solo, and two young women paddling tandem. The man identified himself as Chris Baker—a once U.S. Triathlon Olympic team coach and river guide. Five years earlier, at age 35, he was struck by a car while riding his bike. He was minutes away from death when the ambulance arrived. He physically recovered after months of surgery and therapy, but his memory didn’t. He only remembers scattered bits and things about his life before the accident; others, his friends and family, had to fill in the missing gaps as best they could.

Chris’ medicine for healing is the wilderness. He and his girlfriend Natalie Cloes, plan to experience and document, through photographs and words, every one of America’s 58 national parks—by foot, bicycle, or canoe. Big Bend, and the river which borders it, is national park number one. They have a five-year plan to complete the remaining 57. When they’re not trekking the parks, they live in a pop-up tent atop Chris’s pickup truck. They’ve allotted $1,000 a month over the five year period for expenses. Currently, they are self-supported, so naturally they’re looking for sponsors. Chris’s passion is photography and he is quite skilled at it. You can see some of his work on his web-site (www.chrisbakerphotography.com).

Katie Wolfenden, third member of the team, hails from London. She has been to the U.S. many times; always to experience wild places, of which there are very few, in England.

We enjoyed sharing two campsites with this delightful trio, this being the first time we have ever shared a campsite on the Rio Grande.

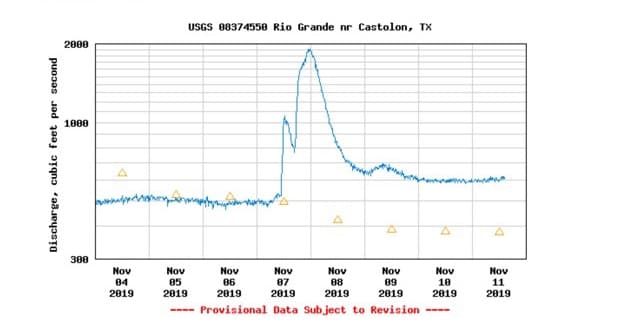

On November 7 we witnessed a spectacular lightning storm far south in Mexico; a few hours later it began to rain at our camp. That night the river began to rise. Fast!

The next day (November 8) it ramped up to 2,000 cfs and was now flooding into the cane thickets and willows that lined the banks. What in the past had been an easy run, was now a challenging undertaking in our tripping canoes.

There were two iconic obstacles that we faced on this stretch of river: Rock Slide (within Santa Elena Canyon) and Tight Squeeze (in Mariscal Canyon). At low to moderate water levels, Rock Slide is relatively easy. But, at higher levels, you’d best be skilled, and very prudent. We carefully choreographed our moves: First, a 20 yard portage (canoe drag) over a gravel (er, mud) bar on river left (the U.S. side), then line the long, heavily-loaded tandem canoe around a short but harsh turn (the shorter solos could be paddled); float into an eddy on river left; then forward ferry across the strong current to the clear channel on the Mexican side. Turn left into the narrow slot and you’re home free. It was dicey but doable.

Two days later, just before we entered Mariscal Canyon, with the river still high and getting higher, we were surprised and concerned to see an abandoned blue kayak on shore on the American side. We didn’t stop, as the current had grabbed us and was taking us quickly within the canyon’s dark walls.

About 100 yards above Tight Squeeze, where the 1,200-foot-high sheer rock walls are practically close enough to touch with outstretched arms, we saw what appeared to be an identical red kayak downstream, wrapped around a boulder in the jaws of the rock jumbled rapid. We pulled smartly into an eddy above Tight Squeeze so as not to run blindly into this dangerous obstacle. What had happened? Where were the occupants of these two abandoned kayaks?

One plausible explanation was that the two kayaks were traveling together—the red one, which was far in the lead--capsized above (or at) Tight Squeeze, and the boat pinned. There was no sign of the paddler so we guessed he got out safely. When the blue kayaker saw the capsize he quickly headed to shore and later connected with his friend. What to do? Our map indicated that a very rough four wheel drive road ran from roughly the blue kayak’s location to Rio Grande Village, 40 miles away. Could the pair be walking the road to RGV? If so, could they carry enough water for a 40 mile hike through the desert? We doubted it. More on this later…

At “normal” water levels, Tight Squeeze commands respect, but it isn’t particularly difficult. But at 2,000 cfs, the water is pushing hard and you can’t see what’s beyond the ordinarily canoeable, narrow slot against the Mexican wall. Safest plan was to portage! We ferried to river left then spent over an hour hauling boats and gear over a mound of big boulders on the U.S. side—first time we’ve ever had to carry around this rapid. And, oh, the mud. Everywhere, on everything. There was no escaping it. Given this scenario, we worried about our new friends—Chris, Natalie, and Katie --upstream. We hoped they were not on the river today.

A short distance below Tight Squeeze, where the river had slowed, we set up camp for two nights in a magically beautiful site deep within Mariscal Canyon.

On our layover day at camp, we inspected the stick we had placed upright at the river’s edge. The crude gauge told us that the water level was dropping rapidly. Good; it should be much safer tomorrow when we continued downstream.

We wondered about the fate of the two unaccounted for kayakers upstream. Concerned that they may be hiking out--a dangerous journey--I called Big Bend headquarters on my satellite phone. I quickly explained the situation we had observed and said I was on a satellite phone in a canyon and could lose contact any second, so please forward my message to the proper park authorities. There was a short pause, followed by, “Sorry, sir, we don’t handle calls like this; you’ll have to call 911!” At this, I went ballistic, reiterating that I was on a satellite phone in a canyon and the phone could go dead any second! “Please, just relay the damn message,” I hollered. Seconds later, the phone went dead.

Around 4 PM the next day the Chris Baker team arrived. Whew! They had wisely camped for two days while the river dropped. Smiles and hugs followed and I made a fine supper for all.

After Mariscal, we had two more days on the river. Our plan was to pull out at Rio Grande Village (RGV) while Chris and his team would finish below Bouquillas Canyon. We shared contact information and Chris promised to send photos.

Day 8 and overcast. The river had dropped substantially but it was still moving fast—so fast, that we were a full day ahead of schedule and RGV was just 12 miles away. Should we camp another night in the mud or hustle to mud-free ground where hot showers awaited? No contest—best speed to the end!

We arrived at RGV at 2PM and immediately set up camp. There are 100 campsites in RGV and nearly all were taken, most with RV’s, but 20 or so with tents. At 4PM the wind began, ultimately reaching 50 miles per hour, with some gusts higher than that. Minutes later EVERY tent (except our North Face VE-25) blew down, breaking poles, shredding fabric, flying off like kites. My solo canoe (Northstar Phoenix) was overturned and tied to a tree; it twisted around on its line several times and would have flown away had it not been leashed. We drove to the little convenience store near the campground and learned that sections of the park were closed and park personnel in the Chisos Mountains area were directed to report to safe quarters.

Just before dark, RV’s began to leave the park in masse.

By morning, there was just a scattering of RVs left in the campground, and zero tents. We had planned to breakfast at Chisos Mountain Lodge, and from there go for a short hike, but with freezing rain, howling winds, and the steep, twisting road up to the lodge temporarily closed due to ice, we just bagged it and headed for home.

On our way out of the park we stopped at the Visitor Center and spoke with the head ranger there. “Did you guys get my message about the wrapped kayak?” I asked. “No, sir,” he replied. Then, I went “calmly ballistic,” suggesting that they should have a MUCH improved protocol for this sort of thing. The ranger agreed and said he’d look into it. We never did learn the fate of the kayakers or the name of the person who took my call.

Additions:

This just in from Katelyn Mahoney, one of the rangers we met on the RioGrande canoe trip. She tells what happened to the blue and red kayaks.

I just read your article on Paddling.com (a friend referred me to it and asked if I was one of the Rangers on the trip - indeed I was). We chatted with your group at Lajitas and downstream of the Rockslide. Glad to hear you had a great trip on the Rio! If you want to know the fate of those kayakers, read on...

So, I did receive a call that same evening from NPS Dispatch regarding your sighting of the abandoned kayaks. Somehow your call was received by a new park volunteer (VIP) at BBNHA - not the NPS Visitor Center/HQ or NPS Interp Rangers. (Hence why they had no idea about the initial report). Nonetheless, the VIP called Dispatch after your conversation, and I got the message. That evening, I checked all known river permits in our system for any potential leads and put gear together for a possible boat recovery in the morning. I drove out River Road first thing the next morning, looking for weary kayakers and/or kayaks. (The blue kayak location was given as further upstream than where it was ultimately located). I worked up and down the river, but was unable to find any people, gear, or foot sign indicating someone had gotten out along that stretch of river upstream of Mariscal. A group of local guides was putting in for a day-trip through Mariscal that morning, and I requested they call with any pertinent info. They located the blue kayak and tied it off, but found nothing else notable.

We reviewed all the river permits, but couldn't find any suitable matches, nor did we receive any reports of overdue parties. (There is always potential for abandoned boats to be associated with illegal border activity as well).

I was already scheduled for a solo river patrol through the Great Unknown and Mariscal and set out. I photographed the blue kayak and its contents for follow-up. I searched Rockpile and The Tight Squeeze area but found no sign of displaced gear or the wrapped kayak. -The red kayak had since freed itself from the jam and was pulled ashore at Solis.

Ultimately, the story behind the ill-fated kayakers was underwhelming at best (but a happy ending overall). As it turns out, the empty kayaks were owned by a couple of young guys visiting the park. They were camping out on River Road and had no river permits (should've had a day-use one), and no plans to paddle through Mariscal. The boats were left near the water's edge, and the owners failed to tie them off. They simply floated away...

Your story is much more interesting though! I hope that this can give some peace of mind as to the fate of the kayakers and that your sat phone call was not made in vain. Take care and happy paddling.

Ranger Mahoney

Related Articles

By now, the term social distancing is something we are all familiar with and learning to adopt. As a…

Follow 3 paddlers and a dog as they paddle some challenging whitewater on the Upper Magnetawan…

Sergi Basoli set off on a kayaking expedition on the Mediterranean Sea and he ended up finding his best…

Earlier this month, I was given the opportunity to travel to Glover’s Reef Atoll - a protected…