- Home

- Go Paddle

- Trip Finder

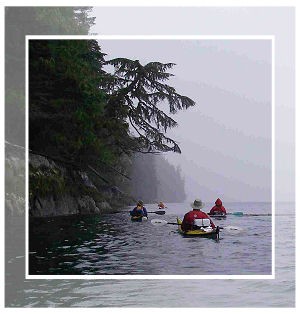

- Great Bear Rainforest (Pacific Coast) in British Columbia

Trip Overview

In late July 2009, Alan Campbell, Robert Dill, Henry Graymen David Maxwell, Mike McMann, Ron Painter, Rob Zacharias and I (Fred Pishalski) headed out into BC's Great Bear Rainforest for a two week kayak adventure. We drove to Port Hardy on the northern tip of Vancouver Island and took the ferry to Prince Rupert, located just below the Alaska boarder. We hired a boat to take us down Grenville Channel where at Hawkins Narrows we started kayaking.

In late July 2009, Alan Campbell, Robert Dill, Henry Graymen David Maxwell, Mike McMann, Ron Painter, Rob Zacharias and I (Fred Pishalski) headed out into BC's Great Bear Rainforest for a two week kayak adventure. We drove to Port Hardy on the northern tip of Vancouver Island and took the ferry to Prince Rupert, located just below the Alaska boarder. We hired a boat to take us down Grenville Channel where at Hawkins Narrows we started kayaking.

The Great Bear Rainforest is a temperate rain forest ecosystem located on BC's rugged and remote west coast. It's 25,000 sq miles in size and the world's largest remaining unspoiled temperate rainforest. An agreement between the provincial govt' and a wide coalition of conservationist, loggers, hunters and First Nations bands established a proposed protected area of 4.4 million acres and another 11 million acres to be run under a managed sustainable plan.

We paddled in the traditional Aboriginal area claimed by the Tsimshian and the Heiltsuk First Nations people. Only a handful of native communities are left from the days prior to 1st contact when villages were scattered along the inlets, bays and rivers of the central coast. Time-honored culturally established intricate social and political structures were supported by highly organized and lavish ceremonies. Native people today however, are no longer able to hunt and gather food in the traditional way. Many west coast native communities became actively involved with the contemporary salmon fishing industry but as a result of a lack of fish, this way of life has also changed. Today many people from these communities have left seeking employment elsewhere.

The Spirit, Kermode or Moskgm'ol (Tsimshian) Bear is also a symbol of this region. The colour variant is due to a recessive gene and the bear is neither an albino or polar but belongs to the black bear family. Tsimshian lore states: "The Creator, Raven, made every 10th bear white as a reminder of when glaciers covered the land therefore people should be thankful for what we have in nature today." Scientists confirm the 10% factor but disagree on just how many white bears can be found on the coast. Ursus americanus kermodei was named after Francis Kermode, a former director of the BC Museum, so the province would initiate research into the bear's existence.

Sea Otters (enhydra lutris) are now seen along this part of the coast. Hunted to near extinction, colonies were re-established on Vancouver Island's west coast in 1970. It is not known if the group on the central coast is left over from the original hunt or part of the re-established group. Sea Otters are a keystone species; controlling sea urchin populations which can damage kelp forests impacting the salmon fishery.

We had arranged ahead of time, for a boat from Prince Rupert to take us down Grenville Channel to Union Passage Marine Park. On Sunday, July 26th we were dropped of at Hawkins Narrows located between Pitt & Farrant Islands. It immediately became obvious that one of our boats was unable to continue. Fortunately we were able to contact, via the VHF radio, the native community at Hartley Bay and our disabled boat and paddler were picked up. He then took the small ferry the next day from Hartley Bay back to Prince Rupert.

We had arranged ahead of time, for a boat from Prince Rupert to take us down Grenville Channel to Union Passage Marine Park. On Sunday, July 26th we were dropped of at Hawkins Narrows located between Pitt & Farrant Islands. It immediately became obvious that one of our boats was unable to continue. Fortunately we were able to contact, via the VHF radio, the native community at Hartley Bay and our disabled boat and paddler were picked up. He then took the small ferry the next day from Hartley Bay back to Prince Rupert.

The group's plan was to kayak down into the sound, along the west side of Campania Island, cross to Surf Inlet, over to west Aristazabal Is, down Laredo Channel, east Princes Royal Is, thru Meyers Passage to Klemtu in 2 weeks.

Our 1st camp was at the south end of Union Passage at Peters Narrows. Not only was it exceeding bug infested but we also cooked dinner in the dark. The next morning we headed out into Squally Channel on the southeast end of Pitt Island and paddled down to Cherry Islets. We left our 2nd camp the following morning and fought rough seas both in Otter Channel and Estevan Sound down the west side of Campania Is.

Rob Zacharias brought his newly constructed 2-3 person cedar kayak on the trip. He did a fine job building the boat which handled exceptionally well in all types of seas.

The weather the 1st week was in the upper 80s and as we were paddling in a rainforest, this was unexpected. In this heat, carrying and drinking enough water became a concern for us. We had a new gravity feed water filtration system that mostly worked well.

Our 3rd camp, on the beach just off McMicking Inlet on Campania Island, became our home for three sun filled days/nights. Sleeping late, lazing around, reading, beach walks and short paddles became the order of business during our stay. Unfortunately the bugs were still with us and we used whatever we could to minimize their biting.

Because of bears in the area, we hung our food at night. Some kayakers keep their food in their boat but a hungry bear can easily rip a fiberglass kayak to pieces. We also found fresh wolf tracks on the beach while camped here.

During a trip to look for water at a stream's mouth, we came upon an old native stone weir system used for trapping fish. At high tide fish would swim into the enclosure and as the water drained, get caught.

Up at 6:00am we broke camp early and paddled down to the southern tip of Campania Island and out into Caamano Sound. This was our first major open water crossing of the trip and I'm usually nervous when doing one of these. We had light winds that dropped to nothing by the time we reached the other side and the Duckers Islands where we stopped for lunch.

Up at 6:00am we broke camp early and paddled down to the southern tip of Campania Island and out into Caamano Sound. This was our first major open water crossing of the trip and I'm usually nervous when doing one of these. We had light winds that dropped to nothing by the time we reached the other side and the Duckers Islands where we stopped for lunch.

Our 4th camp was on one of the Sager Islands, located between Emily Carr Inlet and Surf Inlet. We had to remove a dead tree and clear an area for our kitchen but this turned out to be a pretty nice camp with almost no bugs. We remained here for three nights, resting our sore paddling muscles. For a bunch of guys living out of kayaks we eat very well, each taking turns cooking a complete dinner with wine for the crew.

Up again early, we headed down along Princes Royal Island then 8kms across Laredo Channel. We encountered winds as we got closer to our 5th campsite at Baker Point on Aristazabal Island. We camped in the lee of the point to avoid the strong winds blowing down the channel. The island is named after Spanish officer Gabriel de Aristazabal by Commander Caamano who named the sound just north after himself.

We stayed at Baker Point two nights. On our 2nd day, we hiked along the shore looking for a creek shown on the charts. Robert went out fishing and brought back a very nice salmon, which quickly became dinner. The only other kayakers, 3 folks from Washington, we encountered while out paddling camped near us that night and got invited to our salmon dinner.

We slept in the next morning so didn't leave Baker Point until 11:00am. Unfortunately both the current and strong winds were against us all the way down Laredo Channel. We stopped for lunch with the magnificent rainforest at our backs and waited for a while hoping that the winds would die down, which they didnt. We crossed Laredo Channel just north of the Ramsbotham Islands in rough seas and stopped for the night on Princes Royal Island at around 7:00pm.

Our 6th campsite was on the abandoned Kinmakanksk Reserve. The ruins of an Aboriginal long house still remain on site. Corner logs still hold up two enormous cedar logs running along the edges of the dug out centre of the old structure. We later learned that this was a meeting or trading house for the various tribes in the area.

The bay that we stayed in was completely protected from the winds out in the channel and it was obvious why the First Nations people selected this spot to build their long house. When we arrived a Raven greeted us with lots of noise. I half joking asked if we could have permission to spend the night as we were just tired paddlers heading south. That evening, unlike the others I was the only one not bothered by bugs; I had had a bath in the ocean though.

After the fog lifted the next morning, we paddled south out of the channel into Laredo Sound stopping at Laidlaw Island for lunch. We continued on to Milne Island, our 7th camp.

We had planned on 2 days here in case we had bad weather someplace on the trip, which may have forced us to layover until it cleared. Our 1st night here we heard wolves howling in the distance. Rob again caught another large salmon, which we added to our collection of muscles gathered at low tide. One of the kayakers from Washington showed up just in time to share in our dinner feast. We also had a bear briefly visit us but moved quickly away once we were spotted.

We had planned on 2 days here in case we had bad weather someplace on the trip, which may have forced us to layover until it cleared. Our 1st night here we heard wolves howling in the distance. Rob again caught another large salmon, which we added to our collection of muscles gathered at low tide. One of the kayakers from Washington showed up just in time to share in our dinner feast. We also had a bear briefly visit us but moved quickly away once we were spotted.

In light rain the next morning we headed into Meyers Passage. We had been told to look for petroglyphs in the narrows but the forest was overgrown and we were not able to find them. After kayaking 27 kms, our 8th or last camp was located just off Tolmie Channel on Sarah Island. Near us was a cedar tree whose bark had been stripped and would be used in making Aboriginal baskets and/or weavings.

The next morning we broke camp and paddled to Klemtu. Because of the abundance of sea kelp in the bay, many years ago two separate indigenous groups came together to live in Klemtu or Klemdulxk (blocked passage). The Kitasoo tribe of Tsimshians were originally from Kitasu Bay and the Xai'xais of Kynoc Inlet were a subgroup of the Heiltsuk people. They thrived here in one of the richest most diverse ecosystems found anywhere on the coast.

By the 1870 with the advent of coastal steamer traffic, servicing the logging and fishing camps on the coast, Klemtu became a stop for cordwood for the steam boilers. A fish processing plant and cannery were established in the1920s but are only partially operating now. Today Klemtu with a population of 420 is attempting to reach out and bring in ego-tourism business by providing a wide variety of multi-day tours and guided adventures (www.spiritbear.com/).

Klemtu's recently built Big House offers a glimpse into the traditional cultural and is used by the community to hold celebrations, traditional dances/potlatches and memorials. It has allowed the people of Klemtu to share their stories with others, to reconnect with their history and to help keep ancient ways of life alive. Our group departed Klemtu on the Queen of the Chilliwack ferry late Sunday afternoon. Hot showers, clean clothes and food we didn't have to prepare were just some of treats that were very well received by every one of us. We stayed on the ferry 27 hours until it reached Port Hardy/our cars and then headed home.

As a group this was our longest trip, both in time and distance paddled. It was both exhilarating and at times difficult. An absolutely amazing adventure and personal journey well worth doing.

Until next year!

Outfitting:

Seward, Current Design, Pygmy, NeckyFees:

Two BC ferry rides both around $100 eachDirections:

Drive from Victoria to Port Hardy on Vancouver IslandHired a boat to take us 4 hours down Grenville Channel.

Resources:

The Wild Coast 2 by John Kimantas is a must have as it lists camping spots which are hard to find.Standard charts #3737, 3742, 3724.

Trip Details

- Trip Duration: Extended Trip

- Skill Level: Intermediate

- Water Type: Open Water/Ocean