River Profiling

Let's say you are planning to canoe a river in northern Canada or Alaska. A trip guide, which you got off the Internet, says the rapids are "mostly canoeable". The question is, which ones are not?

A river profile will provide the answers. Here's how to make one:

- First, draw (use a highlighter) a broad line along each side of the river, parallel to your route. This helps you “keep your eye on the road” while you paddle (see practice map).

- Mark the miles from beginning to end. I mark each mile on 1:50,000 scale (1 inch = 1.25 miles) maps and every 4 miles on 1:250,000 scale (1 inch = 4 miles) maps. Mile zero can be at the start or the end—your call. I prefer to start numbering from the end: that way, I can tell at a glance the number of miles that are left to go.

Now, take a hard look at your numbers: Are you too ambitious? The rule on northern routes is 15 miles a day, plus one "down day" in five for bad weather and the unexpected. Now, into my seventies, I think 10 miles a day is a better plan.

- Mark all potential dangers (falls, rapids, dams etc.) that are indicated on the map. Then make a river profile to see how much the river drops per mile.

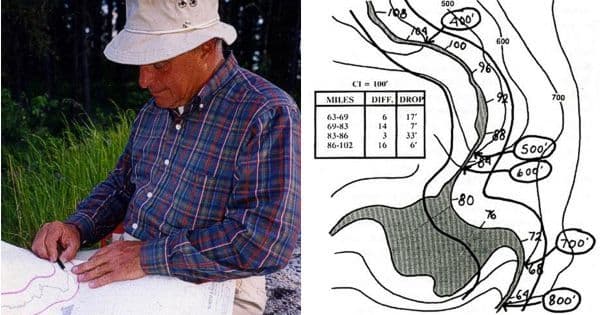

- The contour interval (CI)-- or vertical distance between contour lines-- is given in the lower map margin. It equals 100 feet on the practice map pictured below (Figure 2-1 from my book, CANOEING WILD RIVERS, 5th Edition). This means the river drops 100 feet for every contour line that intersects it.

- Draw an arrow at every point a contour line crosses the river. Write the elevation of the contour next to the arrow, and circle it. The 800, 700 and 600 foot contours, etc. are circled on the practice map.

Make a table like the one illustrated (above), and enter the data. Example: The 800 foot contour line crosses the river at mile 63. The next contour (700 feet) crosses at mile 69. It's 6 miles from mile 63 to 69. Thus, the river drops 100 feet (800’-700’=100’) in 6 miles. Divide 100’ by 6 and you get 17 ft. per mile of drop over this distance.

To continue: The 600 foot contour crosses at mile 83. From mile 69 (the 700' contour) to mile 83 (600' contour) = 14 miles. Divide the 100 foot drop by 14 miles and you get a drop of 7 feet per mile.

To the experienced paddler, drop figures conjure a vivid picture of a river's personality. Three to 5 feet per mile is lazy cruising; 10-15 feet per mile brings a smile; 20 means a probable portage, and 30 or more approaches the limit of an open canoe. Exceptions abound and largely depend upon "how the drops occur" (i.e. whether they are spread uniformly over a long distance, or come as a single falls or short rapid). Rivers that have uniform drops — even in excess of 30 feet per mile — are often pleasantly paddleable. Many Arctic rivers flow at this speed and are nicely canoeable. When I canoed the Kautikeino River in Finland, a three mile section of river dropped 62 feet per mile — and it was "courageously canoeable!" Bottom substrate (sand or rock) is a clue: Sandy bottom rivers tend to erode uniformly and produce canoeable rapids; rocky ones, like those on the Canadian shield, do not.

SOME MAP TIPS

- I use Thompson's Water Seal (available at hardware stores) to waterproof my paper maps. I paint it on with a foam varnish brush then allow it to dry. TWS makes maps completely waterproof — and you can write over them with a pencil (not a pen). I place my TWS-treated maps inside a large waterproof map case which is secured under a length of shockcord on the aft canoe thwart. This provides instant visibility and reasonable security. When rapids loom ahead, I stuff the map case into the nearest pack.

- Map cases: I’ve tried many different ones but my favorite is the one made by Cooke Custom Sewing in Lino Lakes, Minnesota. It's a slightly downsized copy of the giant military map case I had when I was an army liaison officer in Germany. The large, clear-sided (both sides) case accepts up to a dozen, slightly folded, full-sized topographic maps. The nylon case can be folded or rolled. There are attachment points for a carrying strap. The mouth seals with Velcro, so the case isn't 100 percent watertight. But no matter if the maps are pre-treated with TWS.

My book, CANOEING WILD RIVERS, 5th Edition, contains more detailed information on this subject. www.cliffcanoe.com

Related Articles

"Seven days, three rivers, one kayaker: Nouria Newman kayaks solo in India! Nouria Newman combines a…

A chart is not a map. A map just shows you how to get from point A to point B through roads. A nautical…

A handheld Global Positioning System (GPS) receiver can be an extremely useful piece of navigation gear…

The access point on Lake Monson is at the head of a small inlet on the amoeba-shaped, glacial formed…